Students encounter historic and modern conflict with London’s Virtual Classroom

Students on the “Borders in Flux” field studies Signature Seminar consider the relationship between politics and religion in Ireland, what constructs a ‘national identity’, and how the violent past of Ireland impacts the present day. Students explore themes of religious conflict and peace-making within Ireland; the concepts of ‘Irishness’ and ‘Britishness’; and new tensions wrought by international migration and regional politics.

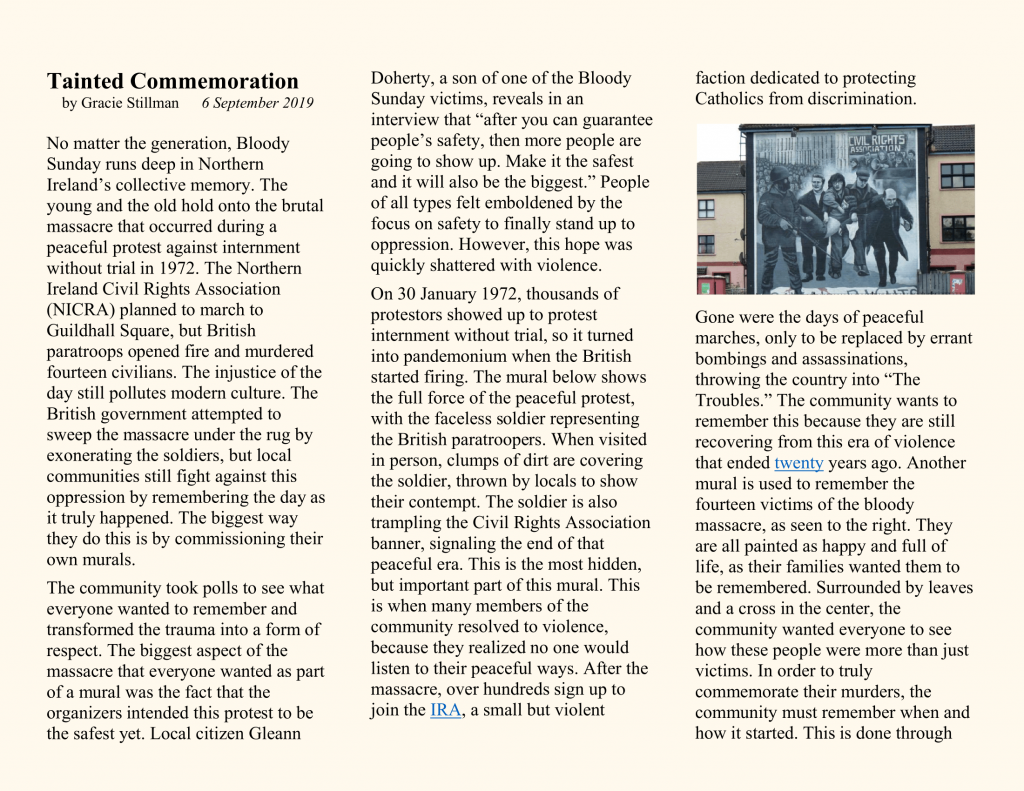

Cycling through downtown Dublin, crossing the Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge, and examining ‘phoenix tourism’ enables students to explore issues like Brexit, the eighth amendment referendum on abortion, and the current economic and housing crisis. Dr Maggie Scull’s creative assignments for this field studies course include a podcast and mock newspaper article as well as a more traditional analytical essay.

Tainted Commemoration

a mock newspaper article by Gracie Stillman

The “Borders in Flux: Identities and Conflict in Ireland” Signature Seminar open to students at both the Florence and London Centers, allowing Syracuse Abroad students to learn more about Europe as a whole and make friends across programs before their semesters begin.

Gracie is a student from Lehigh University who studied abroad at the Syracuse Florence Center in Fall 2019.

Click on the preview of her newspaper article to the left to read more of her work, and compare her account with Spring 2020 student Izzy Cassandra-Newsam’s below.

See more student work inspired by the Signature Seminars on display at London’s Migration Museum as part of our “Questioning Borders” Symposium page.

Bloody Sunday: More than a Story for Tourists

a mock newspaper article by Isabella Cassandra-Newsam

LONDON — To some people, Bloody Sunday is an old U2 song burning a hole in their dad’s vinyl collection, gathering dust in the garage. But for the people of Derry, it’s part of their dark past, one that they have a hard time moving on from.

Bloody Sunday took place on 30 January 1972 in Derry, Northern Ireland when British troops broke up a civil protest against internment by opening fire on civilians, killing 14. The history of Bloody Sunday is deeply engrained in Derry’s present as murals commemorating the event are central to the city; cars drive by them, children pass them on their walk to school, people walk their dogs along the Bogside, all passing the paintings commemorating those who lost their lives in the violence.

Moving on is not an option for those who live in Derry; their lives are consumed with the presence of their city’s trauma – and personal histories – packaged as tourist attractions.

The Bogside murals are a huge draw for tourists to see a physical depiction of the violence and the conflict, narrated by someone with a personal connection to Bloody Sunday.

“I explain what I am, what I do, and then I say my Da was one of the victims of Bloody Sunday,” Bogside murals tour guide Paul Doherty says to the Irish Times. Doherty’s father, Patrick, was the 12th person killed on Bloody Sunday, and though it may be a difficult subject to talk about for a living, he doesn’t see it that way.

“That’s who we are, we can’t change that, but it means people know they’re getting a personal account of what happened,” Doherty says.

However, there are many members of the PUL (Protestant, Unionist, Loyalist) community still living in Derry and take issue with the murals. Jeanette Wark, project manager of the Cathedral youth club, tells The Guardian that “the murals only show one side of the story, omitting how Protestant families had to abandon their homes, and ignoring recent history.”

But that doesn’t stop tourists from filing in to Derry’s Bogside to see the murals, as well as the Museum of Free Derry, which had over 1,000 local and foreign visitors in the first week of its reopening, according to the Derry Journal.

But that doesn’t stop tourists from filing in to Derry’s Bogside to see the murals, as well as the Museum of Free Derry, which had over 1,000 local and foreign visitors in the first week of its reopening, according to the Derry Journal.

The museum, located on the same street where Bloody Sunday occurred, is filled with documents and artifacts of the tensions leading up to Bloody Sunday, the event itself, and of those who lost their lives.

Walking through the museum tells the (rather biased) story of the members of the CNR (Catholic, Nationalist, Protestant) community who fought for civil rights and was stopped by British troops on Bloody Sunday, and later the unionists and loyalists of Northern Ireland.

The museum starts with the civil rights movement in Derry, depicting the violence inflicted upon those peacefully protesting, showing pictures of bloody nationalists carrying signs.

From there, you can see the pictures of those shot by British troops on Bloody Sunday, depicting the violence through photographs and videos taken on the day.

Moving from there, you see the following years of the Troubles, through 1998, and even up until former Prime Minister David Cameron’s 2010 apology.

In the museum, you can read about the events, but you can also speak to individuals who have personal connections to Bloody Sunday. John Kelly, brother of Michael Kelly, the second victim of Bloody Sunday works there, ringing up sales of tea and “YOU ARE NOW ENTERING FREE DERRY” pins, but also speaking with visitors, telling them his, and his brother’s story.

While the tourists get a personal account, Kelly, and other family members like him, ensure that the stories of the victims are told truthfully, from those who knew them, adding to the narrative that helps the victims live on through the storytelling in the community.

Additionally, because tourism is such a significant contributor to Derry’s economy, and many Derry residents are employed in Troubles tours and museums, it may seem like it would make it more difficult for members of the community to participate in the commemoration of the events. However, that isn’t the case.

“I’m very proud to do it,” says Paul Doherty. “The family connection is obviously what is there, but in a wider context I’m very proud of Derry as a city which has developed brilliantly in the last 20 years.” Their pride in their stories and history, no matter how traumatic and dark, works well for the city as it relies heavily on tourism to help support Derry’s economy, while also allowing the community to honor those who lost their lives.

Linzi Simpson, council tourism development project officer spoke with the Irish Times, stating that the economic development that Troubles tourism could bring to Derry will also help encourage “engagement across different communities,” something that has been difficult for Derry in the past.

Additionally, it’s the personal touch of the tour guides that makes the experience for tourists, according to Maeve McLaughlin, project manager for the Bloody Sunday Trust’s conflict transformation and peacebuilding project.

Additionally, it’s the personal touch of the tour guides that makes the experience for tourists, according to Maeve McLaughlin, project manager for the Bloody Sunday Trust’s conflict transformation and peacebuilding project.

“People who come here want to hear the stories… and they want to hear people’s experiences,” McLaughlin said to the Irish Times. It’s the personal touch that is what draws people to Derry’s tourist spots, and makes them more interesting and compelling.

But it’s not just family members that get to participate in the commemoration of Bloody Sunday (in fact, most of the Bloody Sunday families stopped “marching after the 2010 apology from the government,” according to the Belfast Telegraph). The annual Bloody Sunday march occurs every year, where “thousands of people march from the Creggan to the Bogside,” “retracing the steps of the original march,” according to ITV and the Belfast Telegraph respectively. And with the recent Saville Inquiry and former Prime Minister David Cameron’s acceptance of blame on behalf of British troops, the march is more for members of the community still fighting for the cause, rather than the families themselves.

But it’s also a way for members of the CNR community to publicly demand justice for those who died on Bloody Sunday, even after the 2010 apology.

“The perpetrators need to go to court and they need to face trial for what they did that day. We are all entitled to justice,” says Kate Nash, who lost her 19-year-old brother William on Bloody Sunday. The march is a way for the Derry community to band together to fight for justice, just as those marching on Bloody Sunday were attempting to do almost 50 years ago.

While it seems like citizens of Derry are stuck in the past, still trying to deal with the violence and unrest that plagued them for decades, the commemoration for Bloody Sunday helps those connected personally to the tragedy remember their families, and help shed light on the violence to foreigners who don’t know or understand the conflict, and using their stories to help in their continued fight for justice. It’s a form of personal commemoration for those in Derry: to tell the stories of those who died fighting for their rights.