Here, Sophia Perida applies the historical methods she gained with Professor Tames in London to her home street in Los Angeles.

Students bring history to life in London’s Virtual Classroom

In 1800, central London’s Bloomsbury neighbourhood was little better than a swamp. A century later, it had become the intellectual and cultural powerhouse of the world’s biggest empire. Local residents are among England’s most famous names: Dickens, Darwin, Yeats, Woolf. Thousands have journeyed from all around the world to study here, including Gandhi, Kwame Nkrumah (first Prime Minister of independent Ghana), and Paul Robeson (the African American superstar bass, actor and political activist).

The London’s Living History class explores how this change came about. Students walk in distinguished footsteps to immerse in raw materials of history. Weekly tours, field visits, and archival work with primary sources such as news clippings, maps, and street directories help students to examine and write histories that have never been told before.

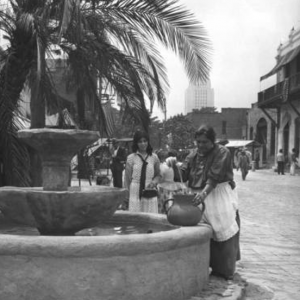

Olvera Street, Los Angeles

by Sophia Perida

Originally, the tiny-but-mighty street, just over three hundred fifty feet in length, was named both Vine Street and Wine Street, after its surrounding vineyards near downtown LA and its notable wineries. In 1877, it was renamed to Olvera Street in honor of Augustin Olvera (1818-1876), who held the first county court trials in his nearby home, and over time deteriorated into a rundown alley. In November 1928, Christine Sterling (1881-1963) was taken in by the historical value of the forgotten area. Her efforts to preserve Los Angeles’ Spanish and Mexican heritage helped to reenergize the street and saved many of its irreplaceable historical buildings.

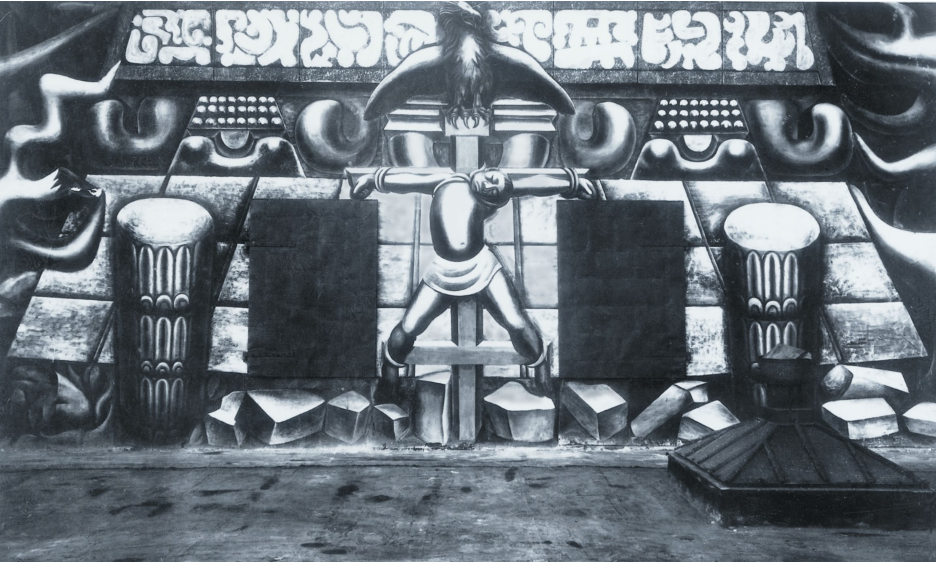

Of Olvera Street’s 27 historical buildings, the Avila Adobe is arguably the most famous. Constructed in 1818 for a wealthy ranchero and former city mayor named Francisco Avila (1772-1832), the Avila Adobe is LA’s oldest house and had been slated for demolition in the 1920’s when Sterling began her work to preserve a “Little Mexico.” Throughout its history, the adobe has been reused and repurposed into various spaces, such as a restaurant and a rooming house. Today, the building functions as a fully-furnished museum and attracts over 300,000 annual visitors. Another example of Olvera Street’s famously repurposed and restored notable buildings is the Plaza Firehouse. In 1884, it was built as the city’s first firehouse but has been partitioned and transformed throughout its history into various saloons, cigar stores, poolrooms, cheap housing and is even rumored to have been a brothel. On the opposite end of that spectrum, the Plaza Catholic Church, built in 1822 and known by locals as “La Placita Church,” remains an active parish and is the only building on Olvera Street that is still used for its intended original purpose.

Additionally, Olvera Street captures the dynamic, active energy of London, in the sense that it similarly subscribes to our history class’s title of “Living History.” In 1930, Sterling successfully fulfilled one of her biggest goals for the area, which was to turn Olvera Street into a stereotypical Mexican marketplace. After being closed to traffic and turned into a completely pedestrianized lane, this street became an instant tourist attraction. Featuring many booths and stores that sell traditional Mexican and Spanish food, ceramic art, clothing and accessories, and souvenir trinkets, Olvera Street and its popularity continues today. For example, the Casa La Golondrina Café, opened in 1924, is the city’s first official Pan-Mexican restaurant and still regularly serves tourists its enduring specialties, such as chicken mole and cochinita pibil (a slow-roasted Mexican pork dish). Additionally, the street regularly features traditional music performances and hosts annual processions to celebrate traditional Mexican and Spanish holidays, such as Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) and Las Posadas (a nine-night procession honoring Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem).

Overall, though Los Angeles is not nearly as well-documented as London, pockets of historical treasures can still be found thriving in places like Olvera Street, allowing today’s LA residents and tourists to participate in and preserve the city’s historical roots.