“Kaitlin draws from a variety of media platforms and sources to craft persuasive arguments about individual and group power in digital spaces. Her work is all the more relevant given the COVID-19 digital shift.”

Students reflect on digital citizenship in London’s Virtual Classroom

In an era of “fake news,” threats to the freedom of the press, big data, and user-generated content, professional journalism faces unprecedented pressure to retain users’ trust and redefine its role in the 21st century. At the same time, technological innovations have led to new ways of storytelling across a variety of British media. In Digital Britain, students look at how British media are evolving in the digital age, finding innovative ways to engage audiences. During site visits and guest lectures, students roadtest a variety of digital projects, develop an understanding of contemporary pressures facing the media industry, and examine how British journalism stands out in a noisy online world.

Assignments in this communications class include academic reviews of digital initiatives in British media, a multimedia report integrating course themes about user experience, and a flexible independent project.

Trolls, influencers, and streaming wars, oh my!

a reflection on internet culture by Kaitlin Azevedo

The internet, as we all know, is a very, very, very powerful tool.

But with power comes huge responsibility.

Up until very recently, I only tended to focus on the negative aspects of the internet. (By “internet” I mean everything and anything related to social media, websites, online journalism, VR… you get the gist). Giving people the ability to be connected all the time, plus the ability to be anonymous a lot of the time, leads to things like trolling and harassment. But what I’ve seen in the past month (I know it’s been about a month of me being in lockdown but I have lost all sense of time, it may as well be years) is that the internet, and every aspect of digital media, seems to be moving toward more positive, lasting impacts.

We’ve discussed a lot of big-picture digital media themes in class, and even with things taking such a drastic shift mid-semester, it actually ended up opening the door to a newer look at the media. Some of the themes that have been discussed all semester, one of which I think has become particularly relevant during the pandemic, are the following:

- Internet Trolls (no, it’s not just teenagers messing around with their friends and making fun of kids online)

- Media Influencers, and what mainstream outlets say about them (yes, there ARE kids on the internet with more influence than the likes of CNN and BBC)

- Streaming Wars (if you haven’t caved in and subscribed to Netflix to watch Tiger King yet, what are you doing?)

In this post, I’ll be going through each of these themes, pointing to some examples that I think truly illustrate what they are and why they’re important to understand. But to make a general case for them: these are topics that will never die in the ongoing discussion of digital media and their effects on people’s lives.

First on the list is internet trolls. When I think of this phrase, my mind defaults to those little ugly troll dolls with the crazy hair and huge eyes, sitting behind a laptop and typing away maniacally in a random chat room. This is very much not the case. We learned that internet trolls take on many forms – recall Alan from the BBC Trending podcast. Alan (a normal guy with a big love for music) was a longtime troll to Gina Miller, a political activist who faced harmful, degrading and downright threatful messages online.

First on the list is internet trolls. When I think of this phrase, my mind defaults to those little ugly troll dolls with the crazy hair and huge eyes, sitting behind a laptop and typing away maniacally in a random chat room. This is very much not the case. We learned that internet trolls take on many forms – recall Alan from the BBC Trending podcast. Alan (a normal guy with a big love for music) was a longtime troll to Gina Miller, a political activist who faced harmful, degrading and downright threatful messages online.

By the end of the podcast we learned that the two sat down face-to-face, and through the troll meeting his target, was able to learn that the two are more alike than they are different. Internet trolls tend to feel more emboldened to harass others on the internet because they feel a blanket sense of anonymity, and even if their names are revealed, there’s always two screens that keep the people separate, making it easy enough to feel like the harm being caused isn’t real.

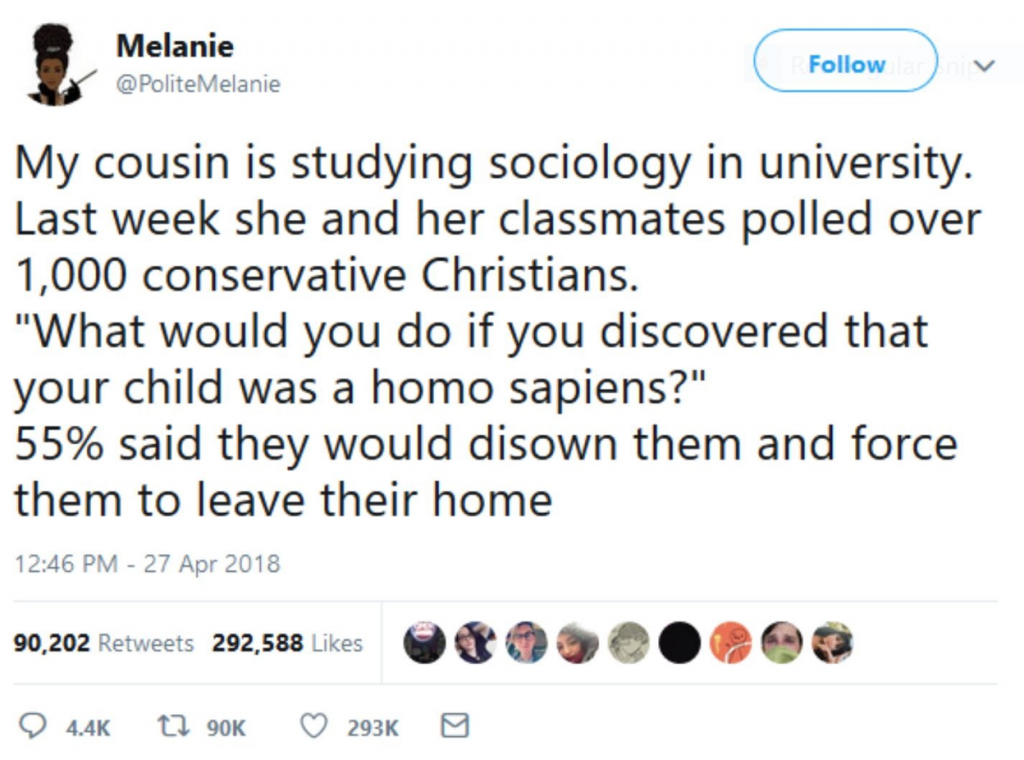

We also learned that sometimes the trolls take a different aim at wreaking havoc. Sometimes, the things said in themselves are not harmful in the slightest, but given timing and context, can unlock entire internet feuds. A perfect example of this is in the Rolling Stones article about Russian trolls sending “uplifting” tweets at just the right time to watch the internet burn. In the case of the Russian-controlled account @PoliteMelanie, the tweets being shared had subtle political undertones, meant to feed into the emotions of people identifying with left-wing political beliefs. The underlying tension? Racism. This is something that the troll accounts used particularly before the 2016 American presidential elections, as the country found itself completely divided between MAGA-lovers and loathers of Trump.

So what exactly is the goal of the Russian trolls? They seek to instill mistrust in the population and to divide people by their political (and coincidentally oftentimes their religious) beliefs. But they don’t accomplish this with the same directed malice of, say, Alan toward Gina Miller. They do so in a strategic and calculated way, by sharing messages that elicit certain responses and let the people jump to conclusions and fight with each other.

In another Trending podcast I found, journalist Ginger Gorman tells the story of her experience “hunting” internet trolls after she received backlash for a feature she wrote on a gay couple, and uncovering the psyche of a troll. She also discussed the role of social media companies in monitoring activity to put a stop to trolling. Gorman said:

There is a very real and valid concern as to how companies can work harder to track trolls and limit what is being shared by them. On a related note, there’s also more work to be done in monitoring the hate we see on a daily basis from people who are simply mean-spirited. It reminds me of the class activity in which we detected comments on Twitter that were inappropriate for whatever category of harassment it fell under, serving as a teaching tool on what kinds of comments and messages are harmful to the internet and promoting hate.

I’ve taken it upon myself to compile a list of tactics for shutting down trolls that we can identify as trolls:

- Report them

- Hold social media companies accountable for protecting their users

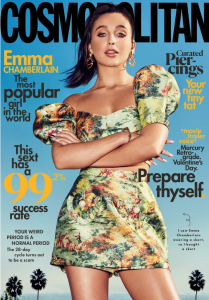

Moving down the list, we have media influencers. I’d like to call 2019 the year of the Influencer. I mean, they’re everywhere now. They’re on Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, Twitter, TikTok… you name it. Look at 18-year-old Emma Chamberlain, who has amassed over 8 million YouTube subscribers and a net worth of nearly 3 million dollars. The success of media influencers is a direct result of the progression of digital media, and its importance in people’s daily lives.

But what exactly is the impact of these media influencers on mainstream media outlets? What is there to say about the relationships these two types of influences have with each other, and with viewers?

One media influencer Bella Mackie was able to share her thoughts on the unexpected lifestyle she now leads, with over 147,000 Instagram followers. The reason why she calls herself an “accidental” influencer is that she began her social media journey with honest posts about her struggles with anxiety. Still, she had to learn how to balance keeping her account authentic, sticking to her original intent for sharing posts, with a newfound job and prestige that comes with the title of “influencer.” Companies now turn to social media influencers to promote products because they have such huge followings, as well as what feels like a more personal connection to their audience.

Mackie wrote in an article for The Guardian:

Still, it looks like she keeps it real on her media, staying true to herself while also allowing it to be a source of work. The community she has built is important because she has the power to send messages to the people who follow her.

Still we are left to wonder how mainstream media feels about the takeover of Influeners. Where do people turn to get news? Who do they listen to most?

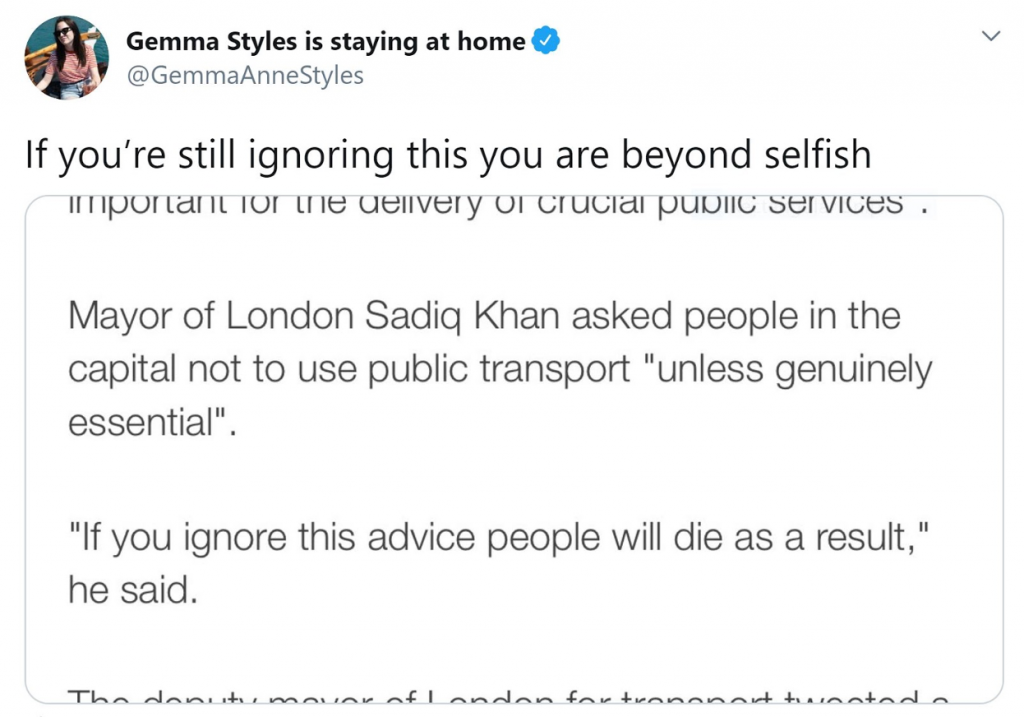

This article from The Guardian explains how influencers are among the main spreaders of coronavirus misinformation, leading to more work for mainstream media in informing the public. In the past couple of months we’ve all seen celebrities and politicians take to social media to share their thoughts on the pandemic – especially since it has become widely politicized. The article notes that according to research by Oxford’s Reuters Institute, “celebrities and other prominent public figures were responsible for producing or spreading 20% of false claims about coronavirus, their posts accounted for 69% of total social media engagement.” Because of this, mainstream outlets have to decide what’s worth disputing. On the flip side, many influencers are doing a fantastic job of spreading real information about coronavirus – especially on the rules of social distancing – which is extremely important as many younger people look up to these kinds of people as if they are the most reliable source of information. Take for instance Gemma Styles (is staying at home) and one of her recent Tweets:

And let’s not overlook her little brother, the one and only Harry Styles, who has chosen to use his platform for good and raise money for COVID relief with a new t-shirt for all the Harries to geek over (I may have bought it – I may be wearing it right now – who’s to say?)

A Bloomberg article explains some of the new challenges Influencers are facing during lockdown. In short, influencers are starting to panic as the companies they promote products for are starting to face the massive economic repercussions of the pandemic: “Luxury brands specifically rely on influencers, outpacing mass brands when it comes to interactions per post.” Well, this is probably a big issue seeing that a lot of people probably aren’t looking to drop a few thousand dollars on a Gucci bag right now.

One last note I’d like to make on the power of influencers comes from our class trip to Arsenal. The visit feels like centuries ago but one part sticks clearly in my mind: “Managing people with huge platforms.” The athletes, while not directly signing up to be influencers, become exactly that by default due to their huge followings. I recall one example of a specific athlete tweeting out a political message, which obviously reached a lot of people. The message included some profanity, which rules against Arsenal’s values for social media interaction. I think this just goes to show how influencers have the ability to cause a lot more buzz than mainstream media.

Moving on: “Joe Exotic” is now a household name across America (at the least) all thanks to Netflix’s very bizarre documentary Tiger King. Millions of viewers stuck at home binged the series; according to Nielsen, the numbers came out to just under 20 million viewers. Quarantine certainly is changing the game of the streaming wars, the ongoing battle to pull in subscribers to streaming services – and what it means in comparison to public broadcast.

Think of all the streaming services you’re subscribed to. My list consists of Netflix, Hulu and HBO (I highly recommend the HBO series Barry – I just binged it and it’s free for streaming right now!) Each one comes with a monthly price that feels like a really good deal for the variety of shows and movies offered, but that price definitely adds up, especially when you’re subscribed to multiple platforms. When guest speaker Jon Farrer from BBC spoke about the challenges of the subscription platforms, he noted that oftentimes there are too many choices and viewers default to things they have already watched before. The struggle is real!

This brings in the whole BritBox thing, which is BBC’s way of entering the streaming wars and creating a platform to compare with the likes of Amazon Prime. There’s a few issues here: money, selection and “nicheness.” Farrer mentioned this in his discussion, basically saying that BBC’s tactic is to present subscribers with a very specific, limited library of options – thus creating a niche category of shows that appeal to a specific audience.

But are people really willing to spend upwards of $50 a month to subscribe to multiple streaming services? Before the pandemic I would have said probably not multiple, maybe one or two. But we’ve seen how the coronavirus has changed the world of entertainment greatly. One Bloomberg article discusses this, saying that even before quarantine, 2020 was going to be the year of streaming. With the more recent introductions of HBO Max, Disney+, Apple TV+ and Quibi, more and more people are cancelling their cable subscriptions (especially because of the lack of live sports) and instead turning to streaming services.

Another article from Bloomberg very interestingly dissects what the rise of streaming services means for the future of TV. To answer the question: ‘Will cable TV die?’ the article says:

Another article from Bloomberg very interestingly dissects what the rise of streaming services means for the future of TV. To answer the question: ‘Will cable TV die?’ the article says:

“More declines in subscriptions. The number of people canceling their pay-TV subscriptions in the U.S. hits a new high almost every quarter. AT&T alone lost more than 1 million customers in the third quarter of 2019.”

But there’s always a catch. Being that many cable providers – such as AT&T and Comcast – are also internet providers, theoretically they can jack their prices for highspeed internet. This doesn’t exactly speak to what will happen with public broadcast stations, though. From what we’re seeing now, I think it’s safe to predict that more and more people will turn to streaming platforms. However, if the world stops burning and sports come back to us, there will still be a need for public broadcast.

How else are people going to watch the Superbowl commercials?

After really diving into the three themes, it’s becoming more apparent to me how significant they are to our daily lives. You don’t have to be an aspiring journalist to feel the effects of the streaming wars, or to be trolled on the internet, or to love (or hate) an influencer. In their relation to digital media, and in these particularly crazy times, we know that these things play a major role in the way people live. What’s most important for us is to be mindful of what we are saying, what people are sharing, and question the credibility of the news we’re consuming as it shapes and informs our thinking.