- See also:

Those words were written by Lianna Meehan, a Syracuse Florence student who went on the Fall 2019 “Borders in Flux: Identities and Conflict in Ireland” Signature Seminar. At the “WALLS” Symposium, the Syracuse London community heard from students like Lianna about their experiences studying walls around the world. The purpose of the evening was to identify the pitfalls of physical barriers — and to question whether there might be any advantages.

Opening remarks given by Slater Ward-Diorio, a marketing student, served to set the scene for the event. As you read Slater’s introduction, click on the presentations he mentions to learn more.

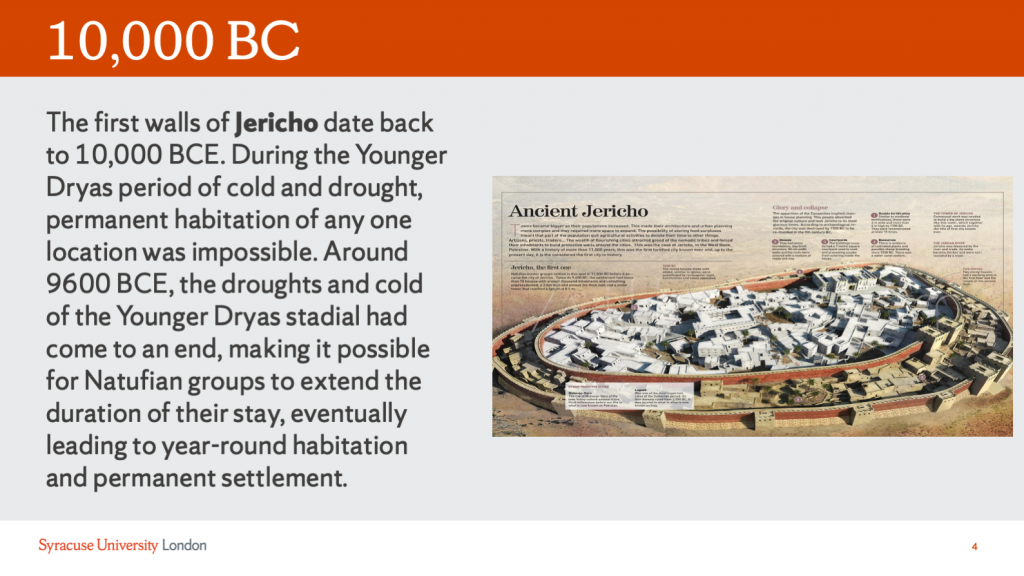

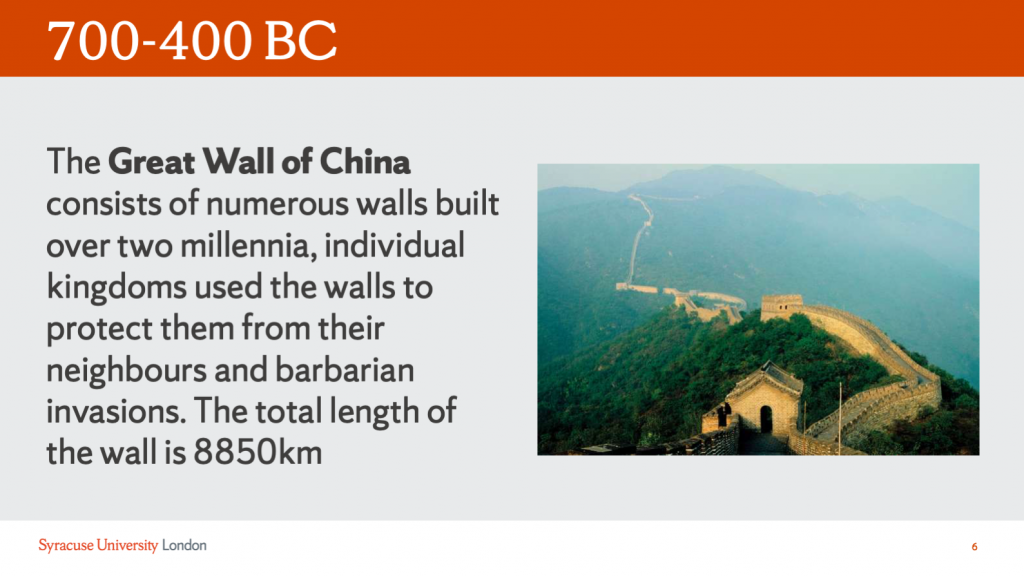

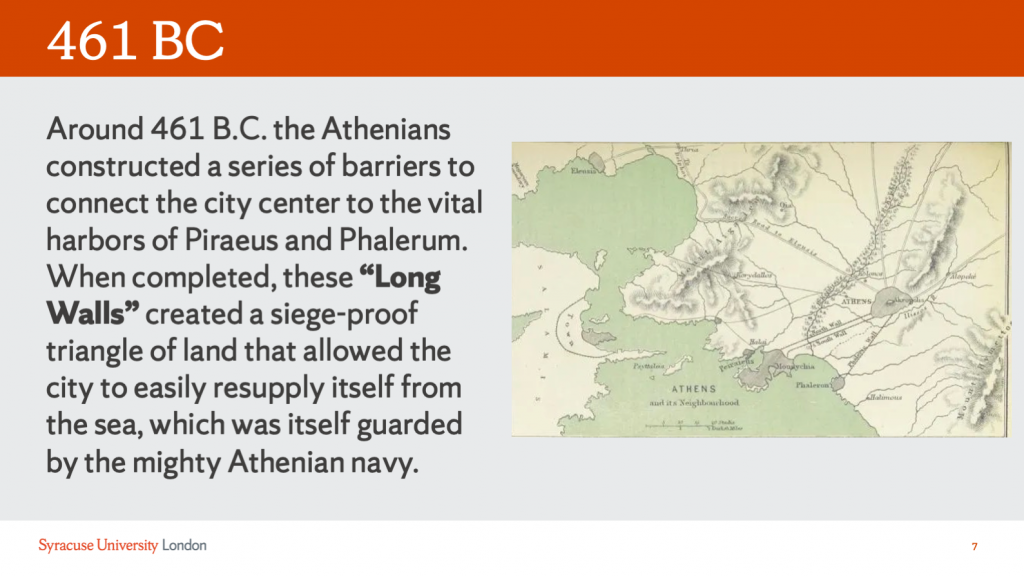

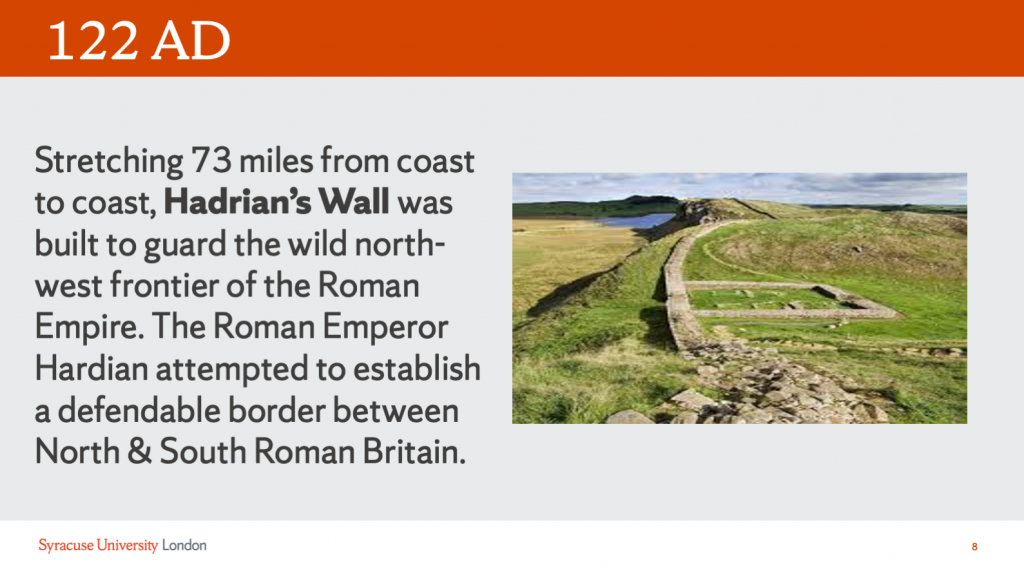

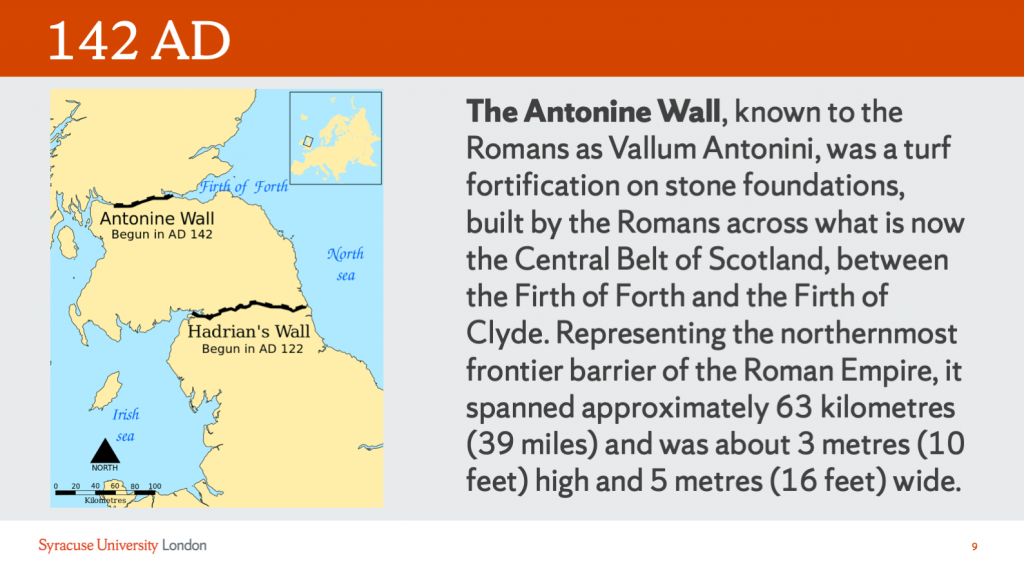

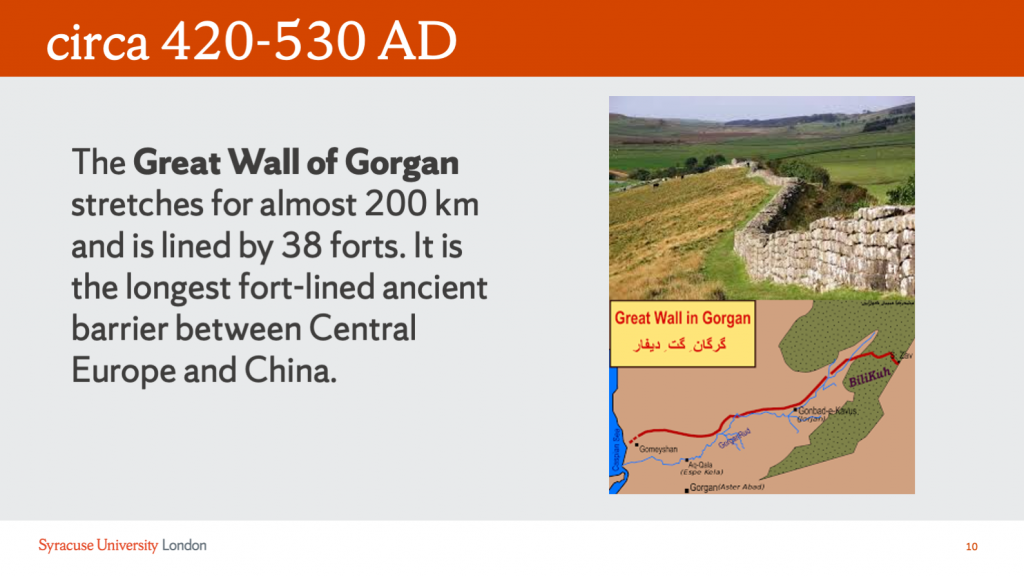

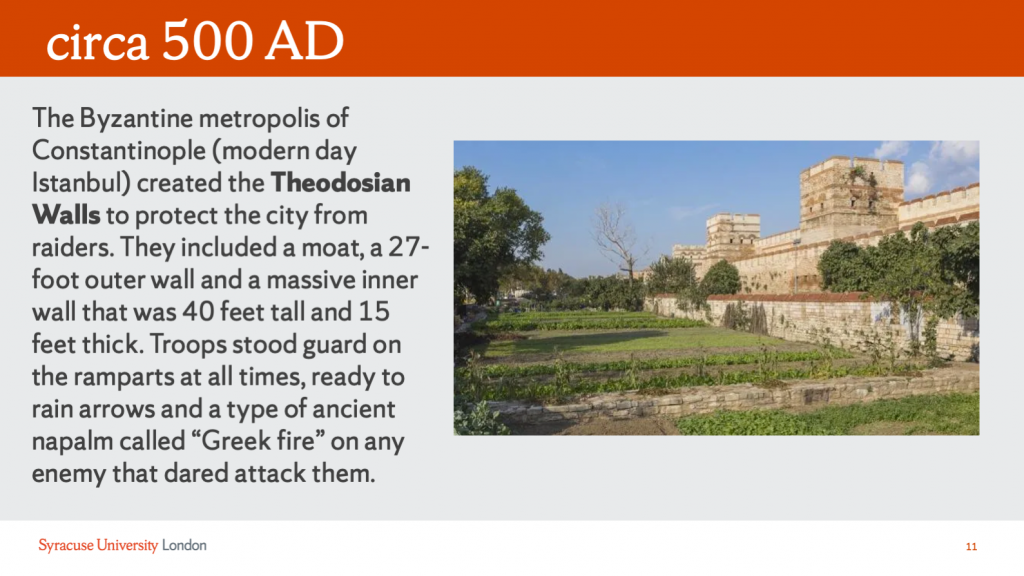

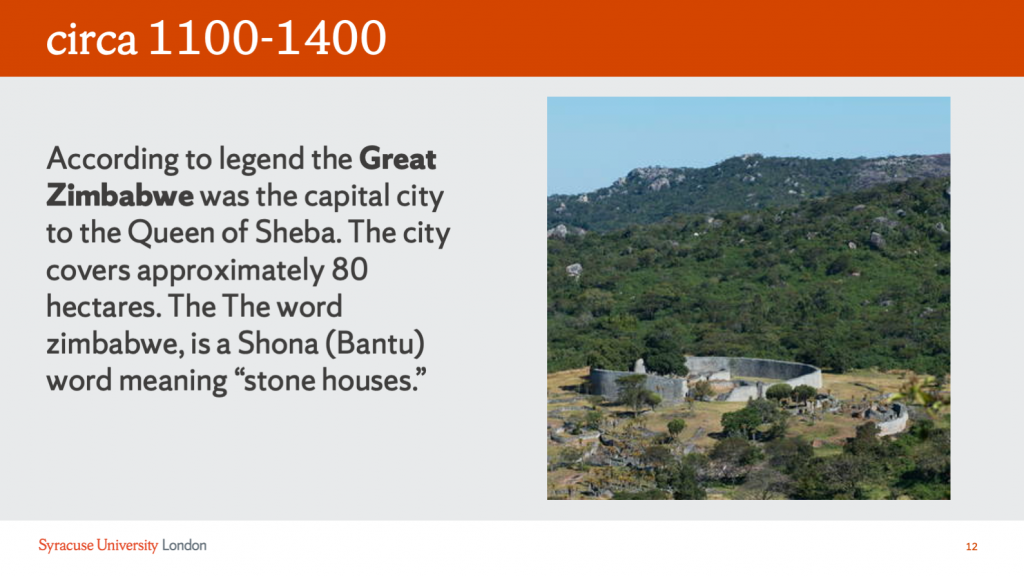

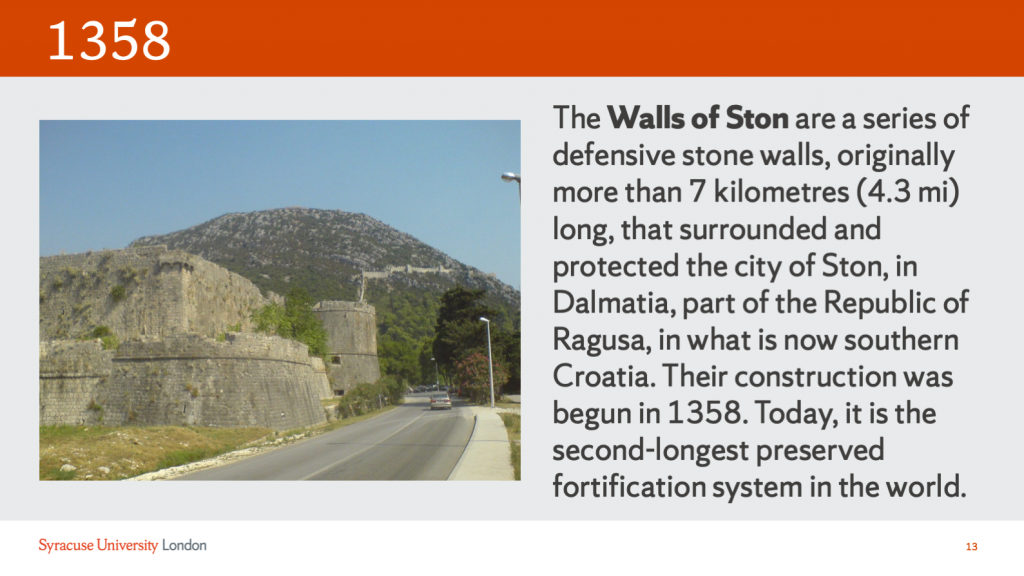

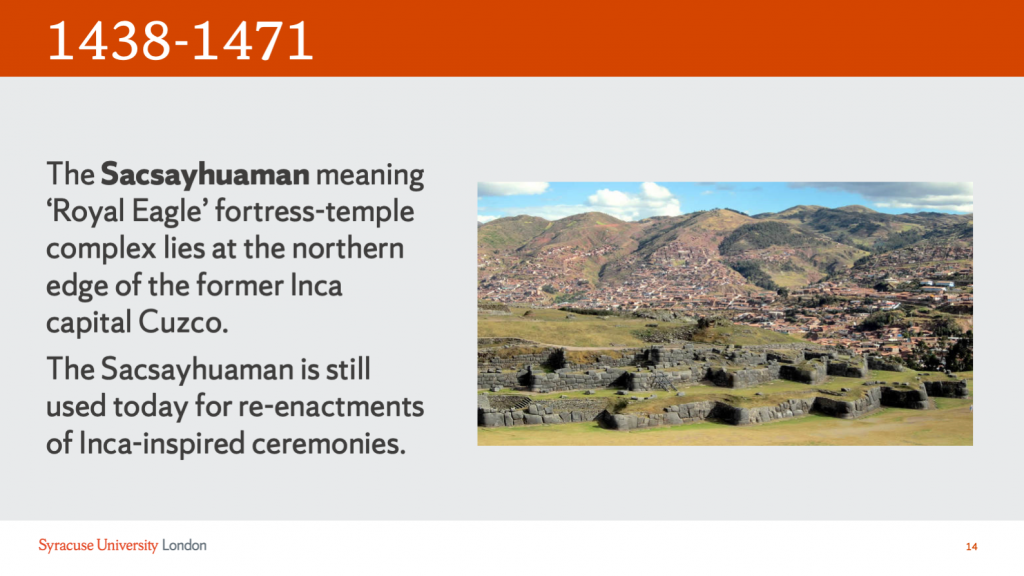

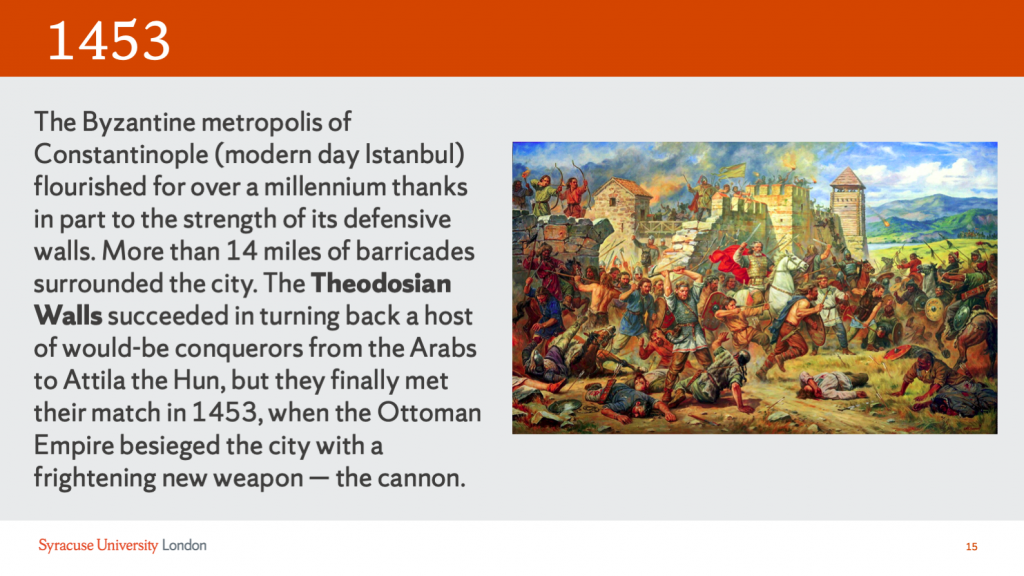

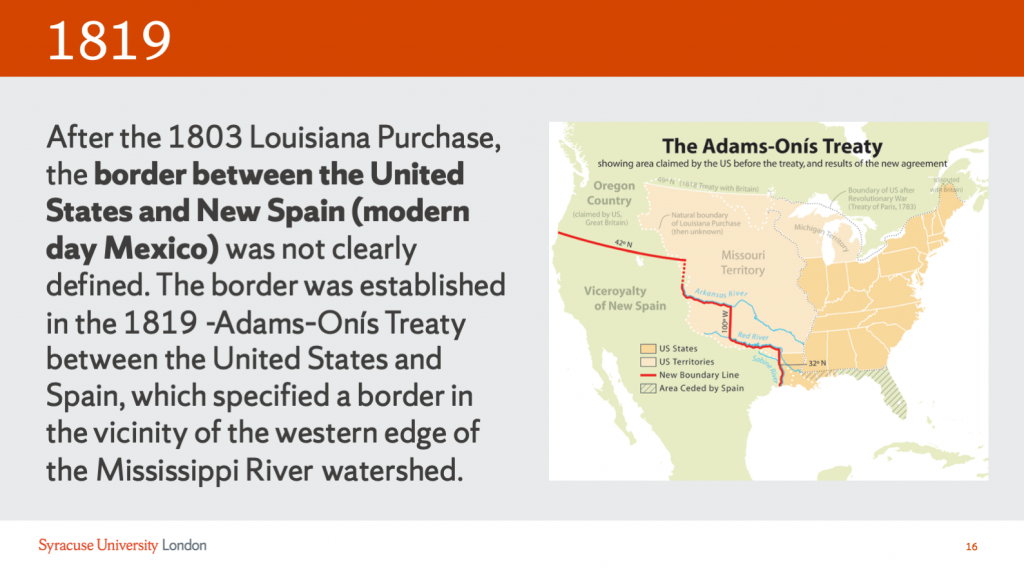

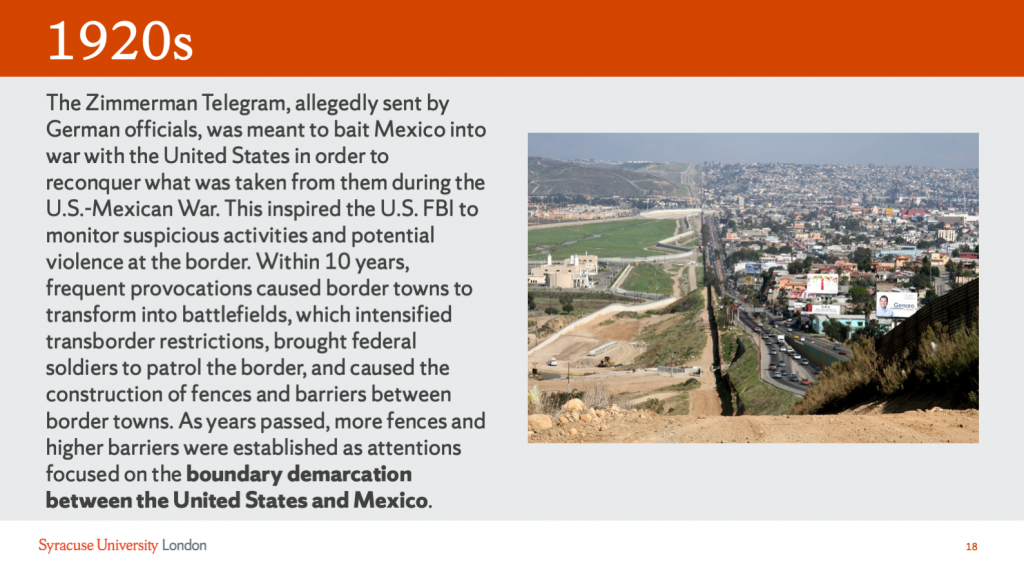

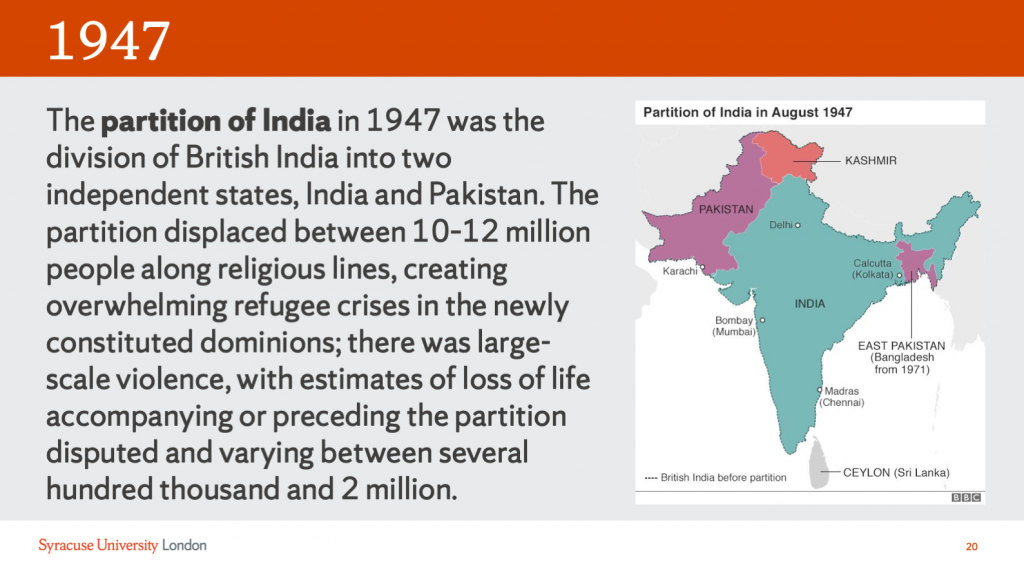

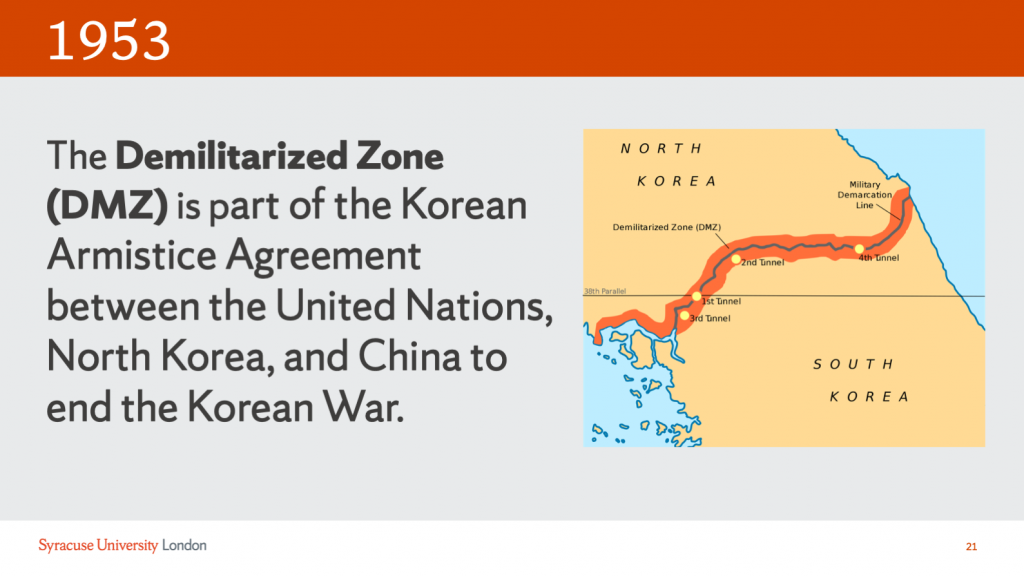

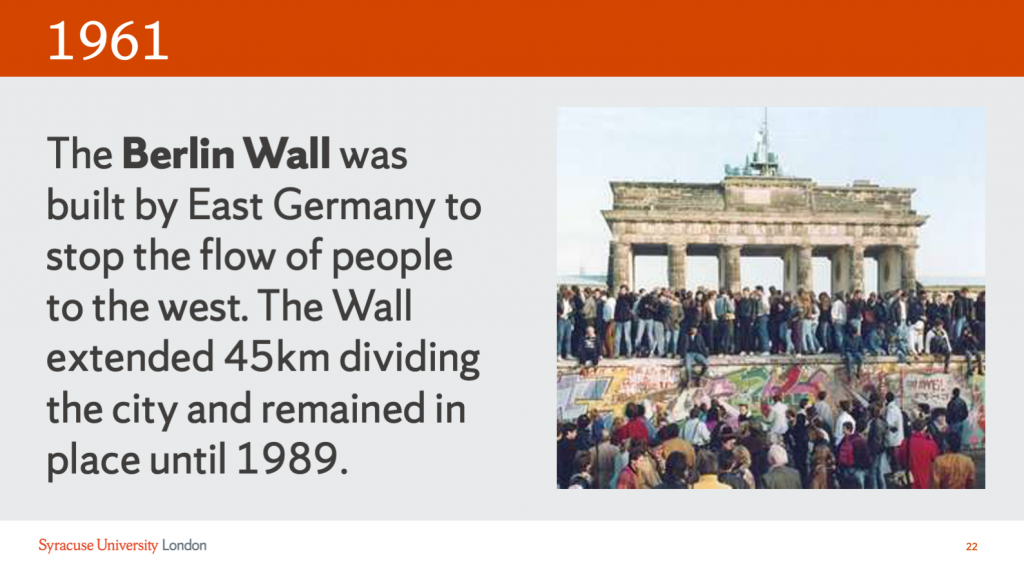

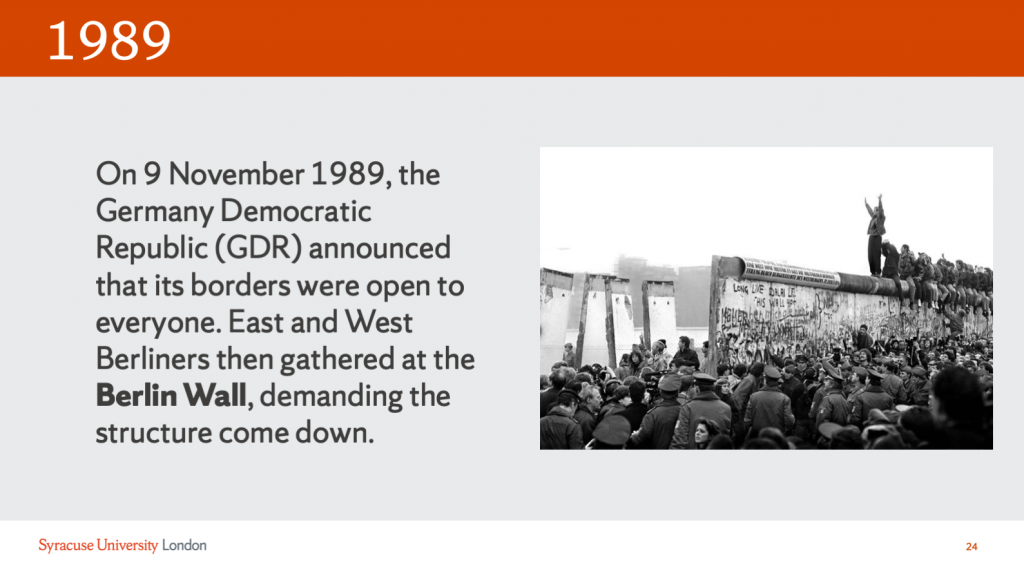

Together, these bits of physical infrastructure tell a stark story about divisions and unification. It is, unfortunately, not a very unique story through human history. As our timeline of “Walls around the World” showcases, people have been building walls for millennia: barriers meant to separate civilisation from barbarism, the good from the bad, us from them. These walls restrict society, but they do not create the restrictions themselves – instead, they mirror and reinforce political, economic, and cultural divisions.

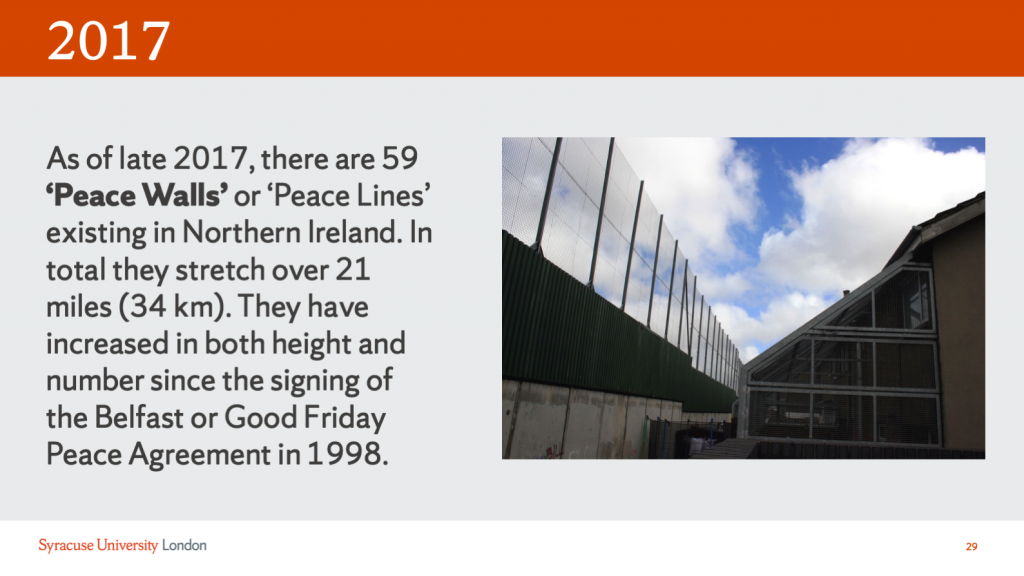

Though I travelled to Berlin this weekend to learn about a historic Wall, I didn’t need to go so far to encounter political division. As the UK wrestles with Brexit and all that entails, the question of Ireland looms ever stronger. I’m particularly excited to hear fellow students from the Ireland Signature Seminar share their thoughts about the so-called Peace Walls in Northern Ireland and how Brexit will impact communities in both Ireland and Northern Ireland. You can read more about their experiences in “The WALLS Gallery” below, featuring creative work from students in both the London and Florence Centers.

While this weekend was a celebratory one, it’s also important to remember that the absence of a physical wall does not immediately end the conflict or segregation. We’ll hear about this from Adena in “The Walls that Still Remain”, and I witnessed it this weekend through measures in Germany like the solidarity tax and continued resentment about Western entitlement.

Many students’ favourite part of the trip was the East Side Gallery, a segment of the Berlin Wall that has been preserved to showcase political graffiti and activist art. As we reflect on these issues, you will have the chance tonight to share a message of how we might build a better wall through our own Syracuse London Graffiti Gallery.

We will then shift our attention to the environmental impact of walls. Juan Montez will quiz us on our knowledge about how physical politics might affect ecosystems, and Suki Lee will share a case study about the US-Mexico border wall. You are also encouraged to check out Joe Saccomano’s poem about dams.

Finally, another student from the Berlin trip, Frankie Sailer, will think about the dichotomy of walls. As you hear from my fellow students tonight, I encourage you to think about the role we have to play in breaking barriers. The Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989 through a combination of politicians’ missteps and activist tactics, but also through the continued push from everyday citizens – many of them students –to imagine something more. Many decades ago, young people in Berlin woke up to a Wall. We were able to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall because people our parents’ age fought for it. Though the Walls remaining in the world may be less near for us, they are no less real. What will we do, today and tomorrow, to create a different world for university students in 2049?

The WALLS Gallery

The Peace Walls of Northern Ireland

by Jackie Doyle

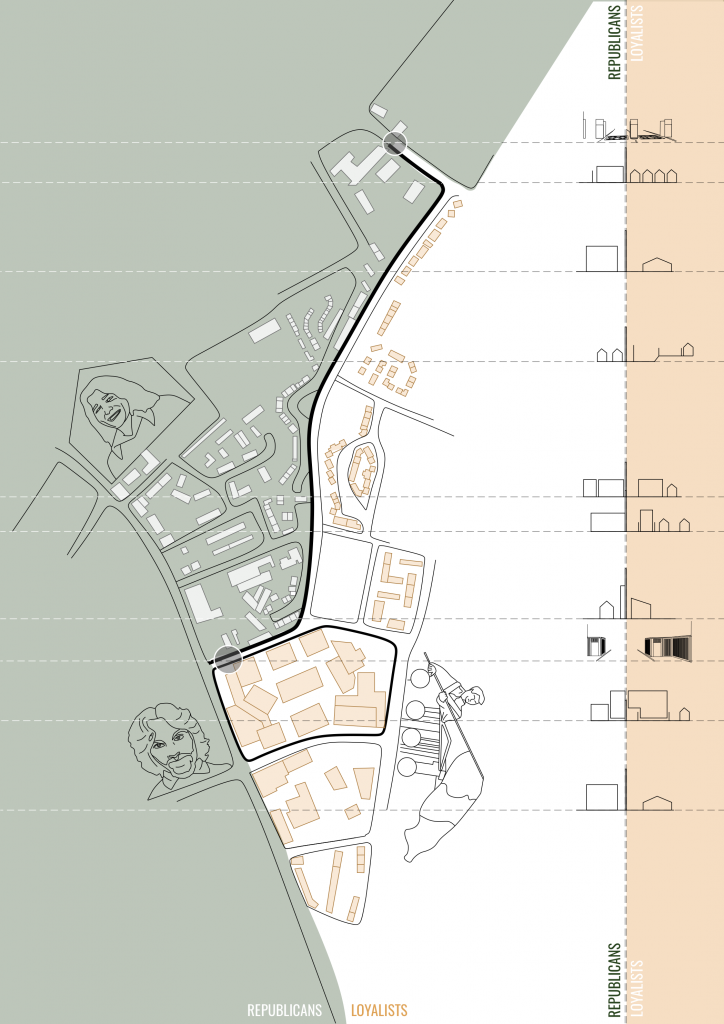

This diagram illustrates one of the longest parts of the Peace Wall still standing in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The graphic shows how the wall divides the two communities — and how sectionally the wall reacts to both sides.

I grew up in a very proud Irish Catholic family and have always been aware of the conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. In fact, my great-grandfather was disowned by his rich and affluent Protestant family because of his marriage to a poor Catholic girl…my great-grandmother. My great-grandfather died young, leaving my great-grandmother struggling to feed four children by herself since her in-laws refused to help, despite living right across the street, simply because they believed in two different types of Christianity. When we visited Northern Ireland, and especially as I walked by the Peace Walls, I found myself reflecting on this part of my family history.

The Peace Walls are structures made out of concrete, stone, and steel measuring twenty feet (six meters) high that segregate Loyalist/Protestant communities from Republican/Catholic communities. They were intended to separate the two parties during the Troubles, when protests between the groups often led to violent riots. After the Good Friday Agreement, the Troubles ended, yet the walls remain.

Today, the so-called Peace Walls are one of the biggest tourist attractions in Belfast, but to me, witnessing them was a very somber experience. The distinct presence of such a wall is intimidating: Though they are meant to be a precaution for peace, walking on both sides feels as though one is trapped and that violence could occur at any moment. They even have gates that close at certain times every night.

When we walked around the Walls, we began on the Republican side. As soon as we crossed to the Loyalist side, I felt my body language and reactions change immediately, thanks to my family’s history. Instead of looking around, I spent more time looking down to avoid any eye contact. I became quieter and smaller as we passed an Orange Order parade.

I became very fascinated by walls due to this experience. Borders are often meant to separate countries, not two different communities of the same country. How can progress be made in a country that refuses, quite literally, to ‘take down their walls’ to come together and talk to each other? I think that perhaps the Peace Walls prevent real progress from being made and hinder the people of Northern Ireland from moving past their grudges from the Troubles. These physical barriers block the mental ones from being fully dismantled, as the Walls act as constant reminders of the past, holding the people back from completely forgiving each other and reuniting as one community. For Northern Ireland to become a more unified and therefore better place, it is important for citizens to understand that it doesn’t matter what your religion or allegiance may be: Together, the people of Northern Ireland stand stronger, whereas divided they fall.

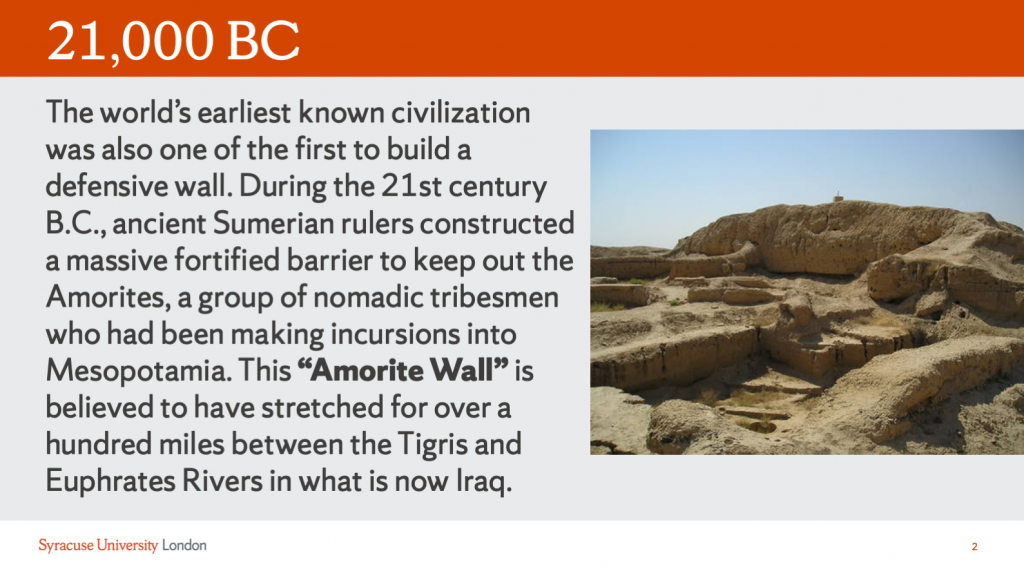

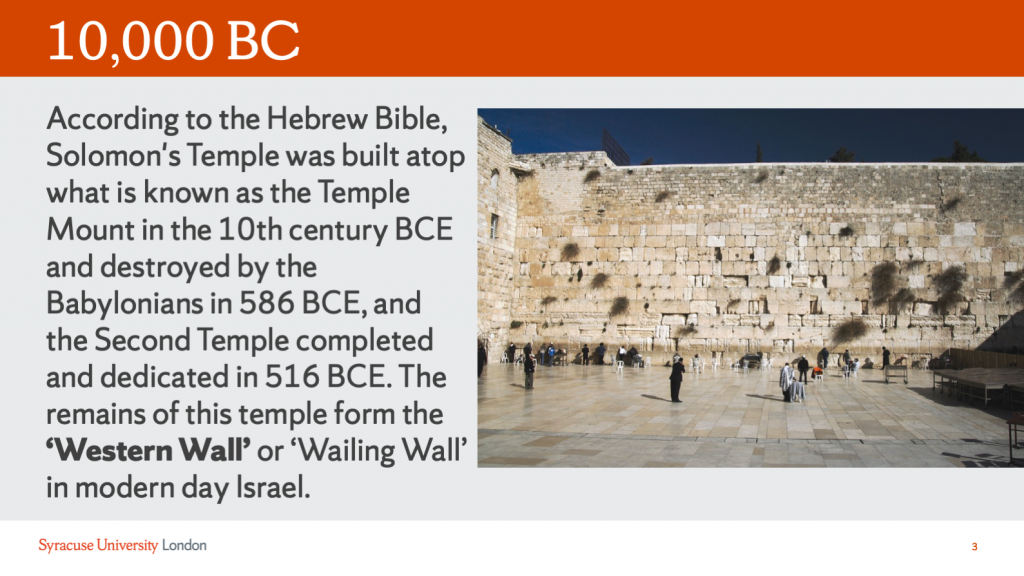

Spanning from 21,000 BC to the present day, Dr Maggie Scull’s partial timeline covers the history of walls around the world – including construction, politics, and impacts.

You can download a PDF of Syracuse London’s WALLS timeline here.

Brexit and all that it entails has raised many questions — particularly for Ireland. The Fall 2019 “Borders in Flux” Signature Seminar students reflected on how Brexit is and will impact communities in both Ireland and Northern Ireland during a panel chaired by Ryan Brady, who used his photography of Peace Walls, political graffiti, cliffs, and iconic sites to facilitate discussion. A sample of his photography is to the right. For more, see his Instagram.

“Dammed, and Damned”, a poem by Joe Saccomano about the impact of walling nature

“Instruments of progress become our damnation”

“Understanding the Family Rift”, a reflection by David McCarthy on religious identities

“a rift ran through”

“Peace Wall, Oh, How I Hate You”, a poem by Lianna Meehan calling for community

“Thirty years have passed”

“I (Don’t Want to) Remember the Wall”, a poem by Ian Dorbu mourning loss

“Like owls, we would chase a new light in a new direction”

“Brandenburg”, a poem by Ian Dorbu remembering division