- See also:

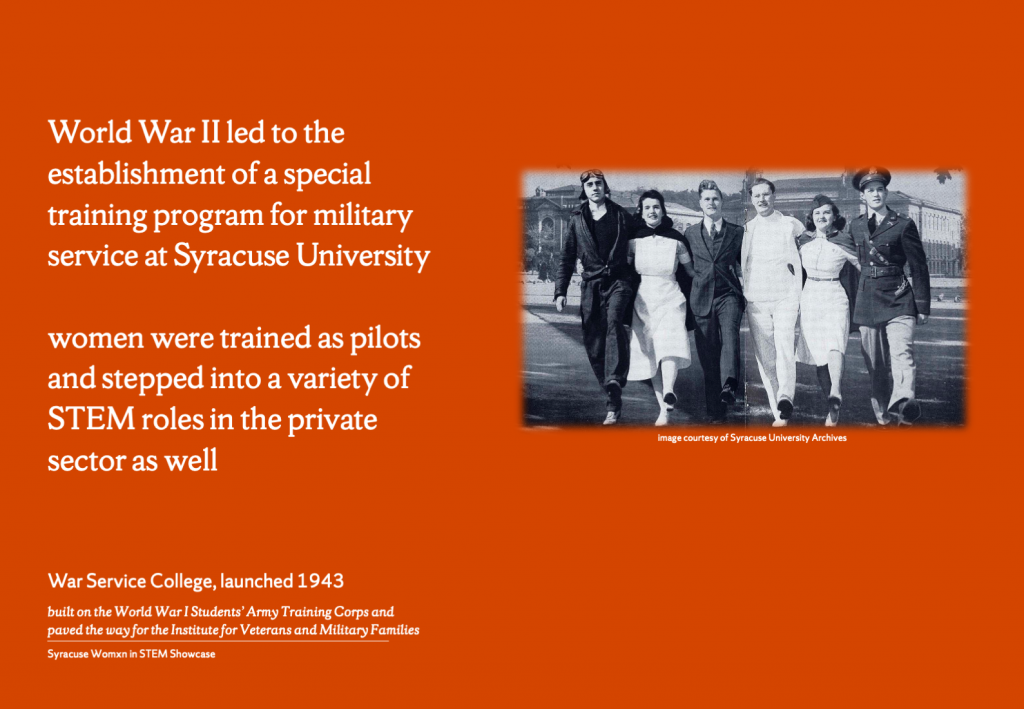

On 24 March 1870, a university in central New York state was founded co-educationally and multi-racially. Dr Jesse Peck’s inaugural speech declared that “brains and heart shall have a fair chance”.

On 7 February 2020, Syracuse London celebrated the International Day of Women and Girls in Science in a special Symposium at Imperial College London that partnered with the Women’s Engineering Society while looking ahead to the university’s sesquicentennial.

However, the history of womxn in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) at Syracuse stretches earlier than the University itself.

In 1847, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to attend medical school in the United States when she was admitted to Geneva Medical College. Every other school she applied to rejected her on the basis of her sex. The faculty at Geneva decided to put it to a vote of their all-male student population. Elizabeth won unanimously, though perhaps in jest. But her graduation was no joke, and the native Brit moved back to the UK to become the first woman on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council. Meanwhile, Geneva Medical College transferred to Syracuse just one year after the University’s launch.

Another regional alum, Mary Edwards Walker, graduated from the local Syracuse Medical College in 1855. Mary holds the distinction of being the only non-male ever awarded a Medal of Honor. It was earned for work as a military surgeon in the Civil War. Dr Walker also worked as an abolitionist and women’s dress reformer – and while we’ll never know with certainty, personal writings suggest that Dr Walker may have identified as trans* and/or non-binary if alive today.

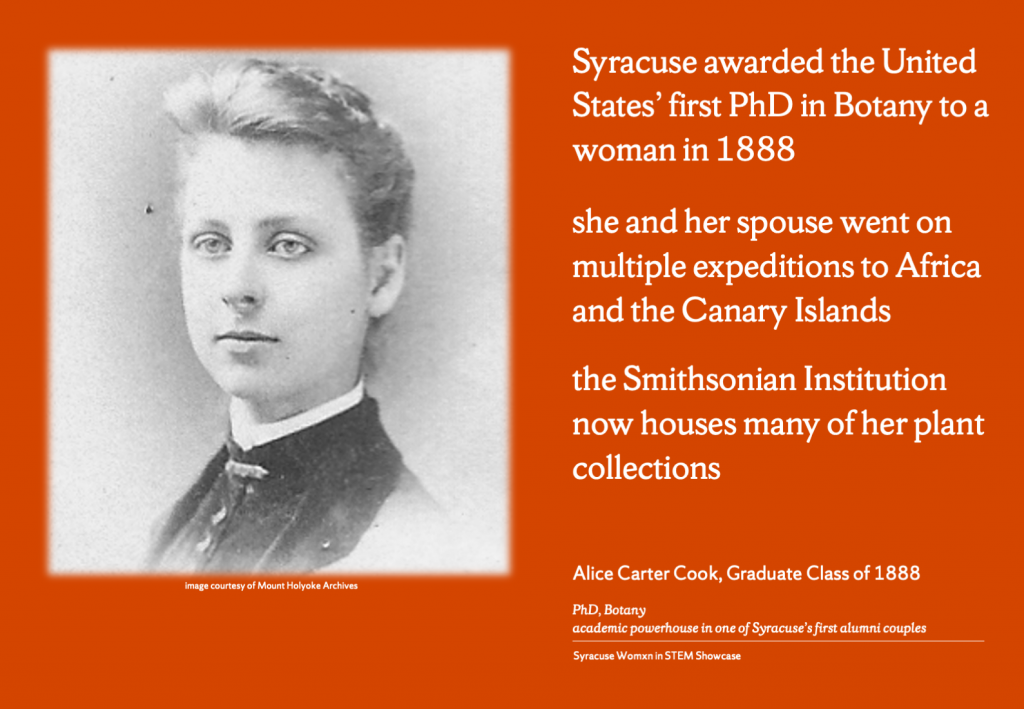

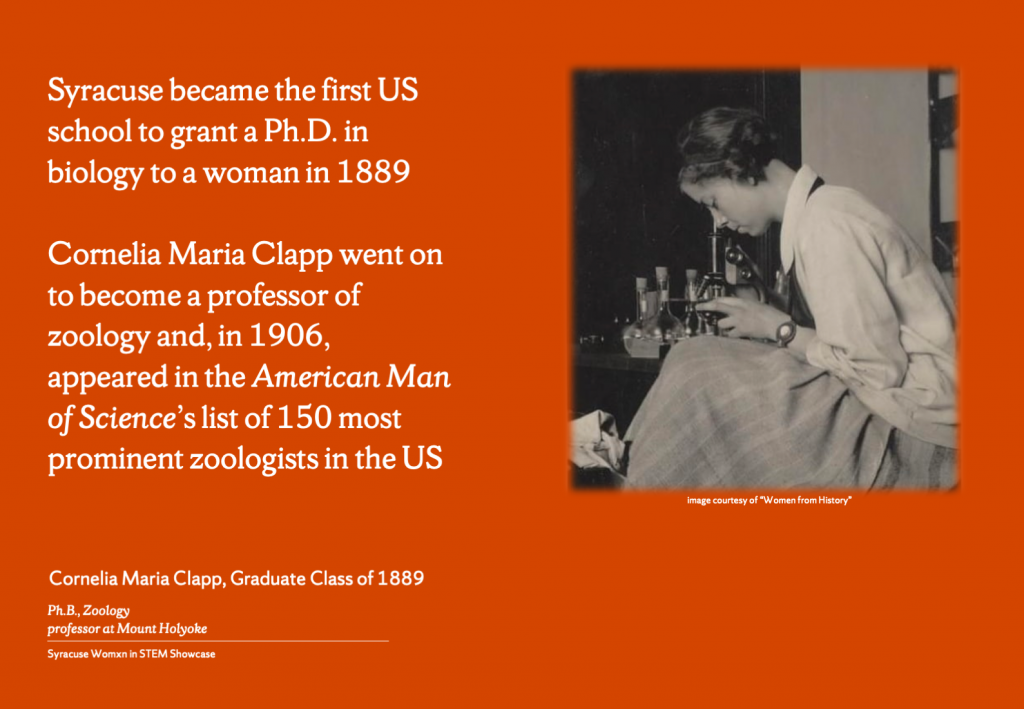

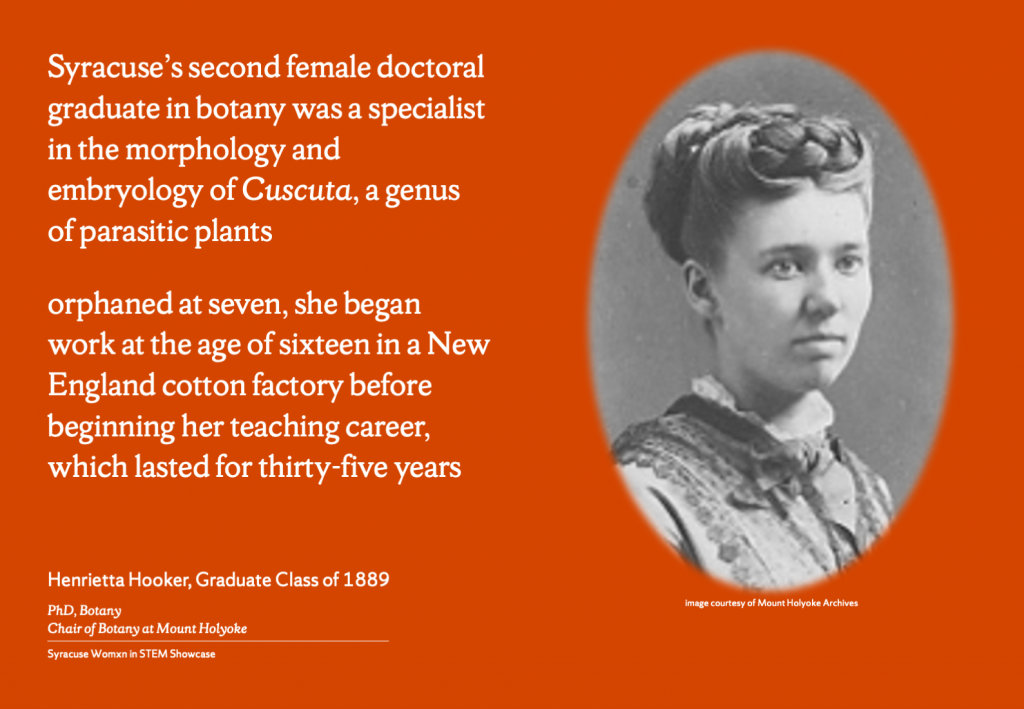

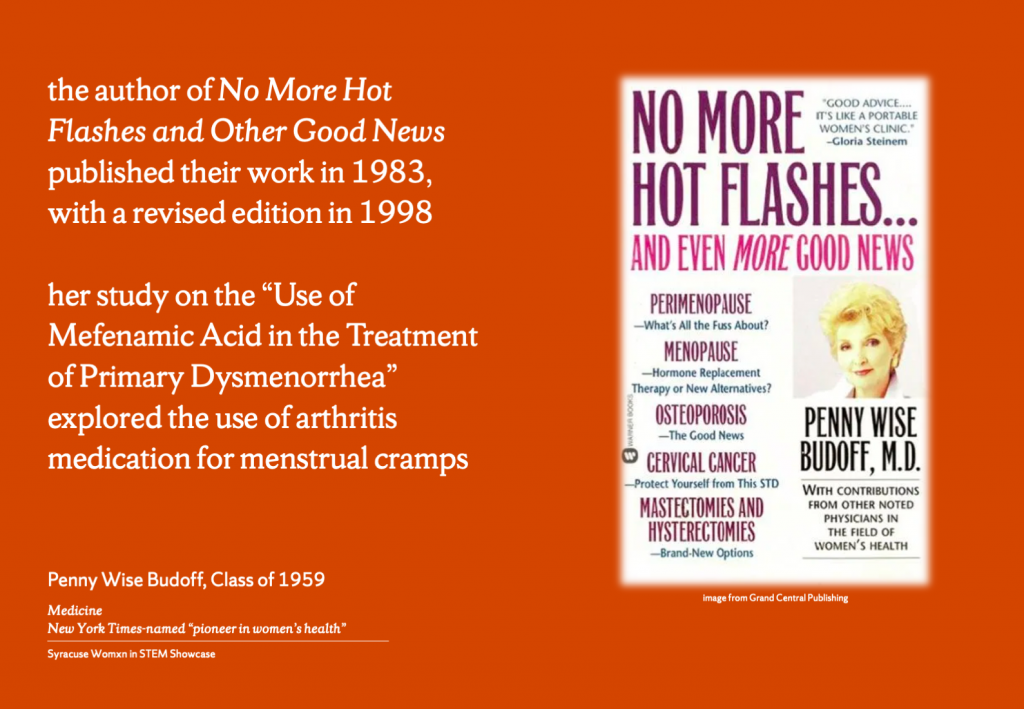

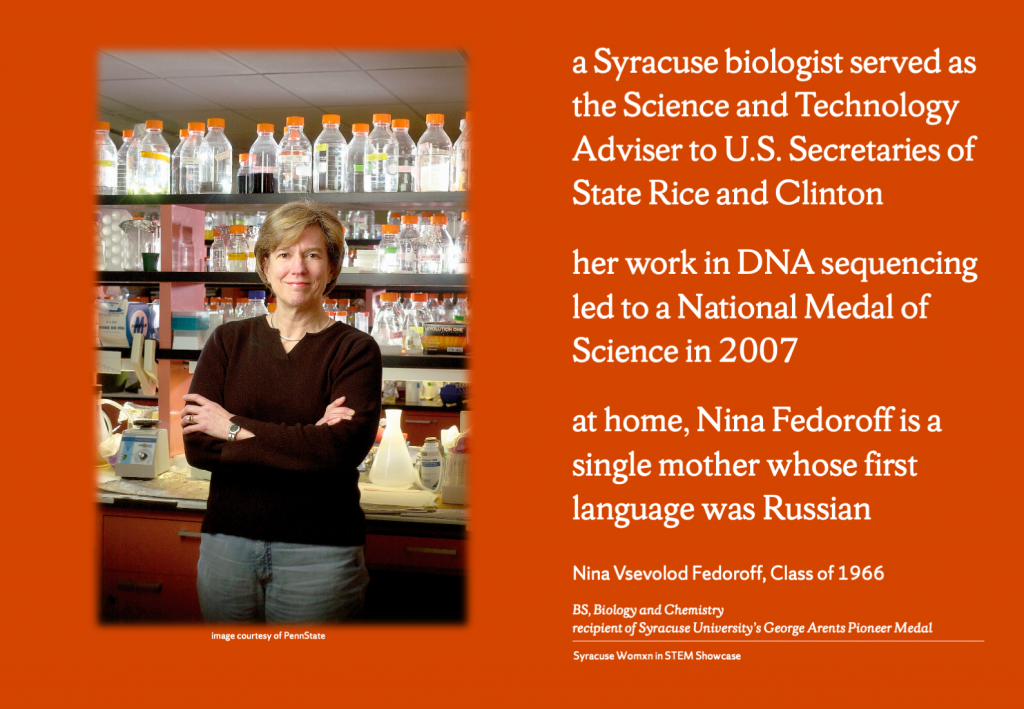

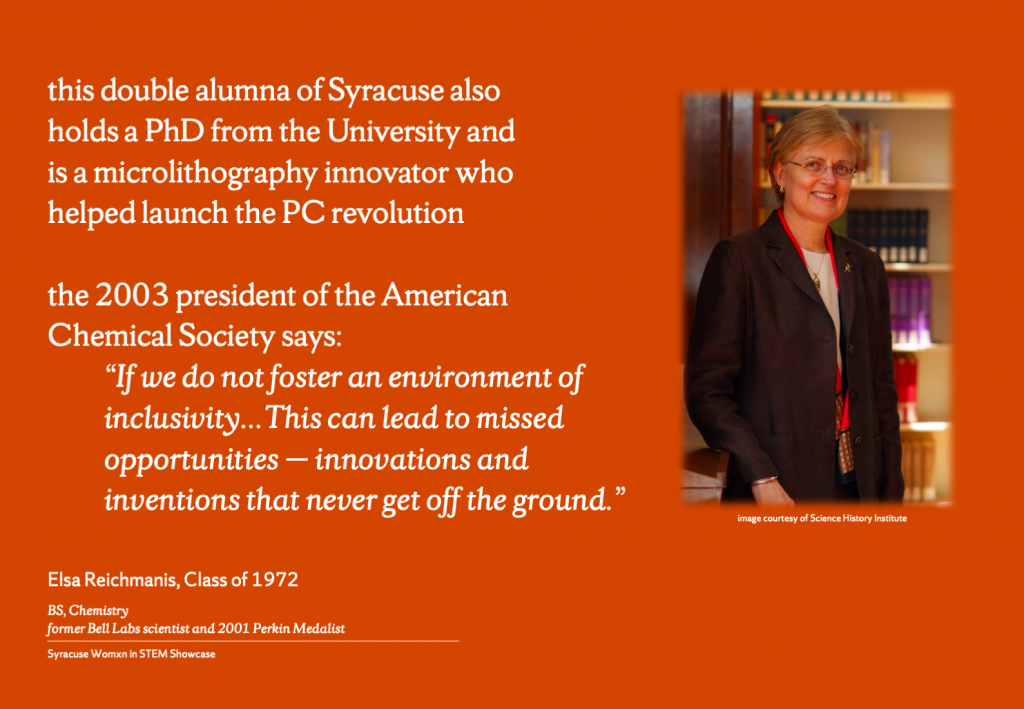

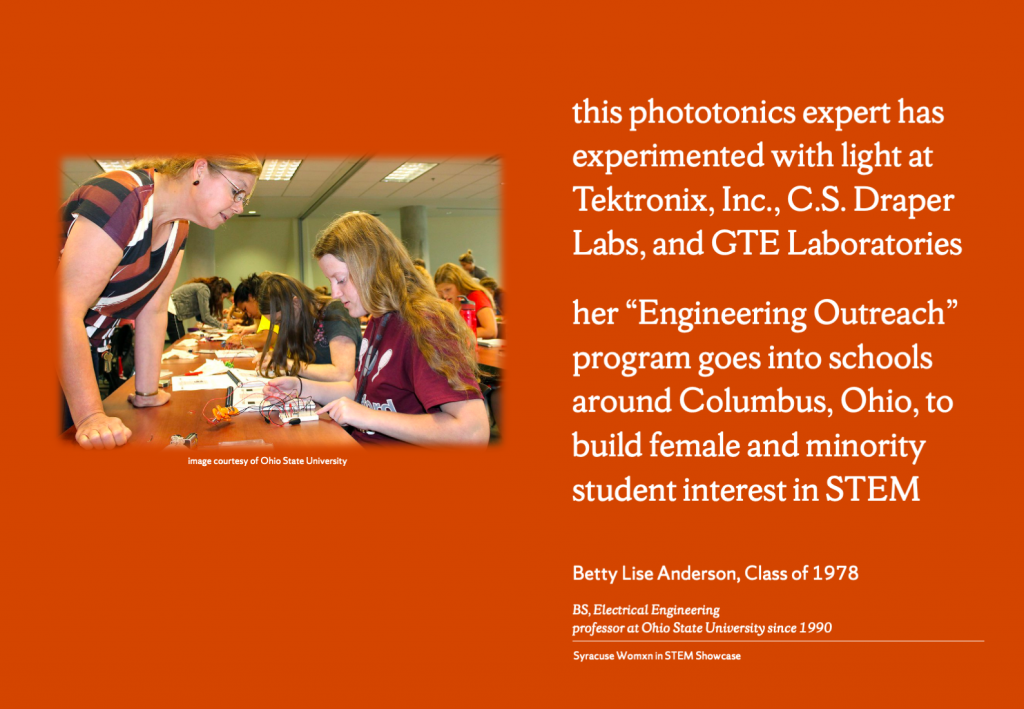

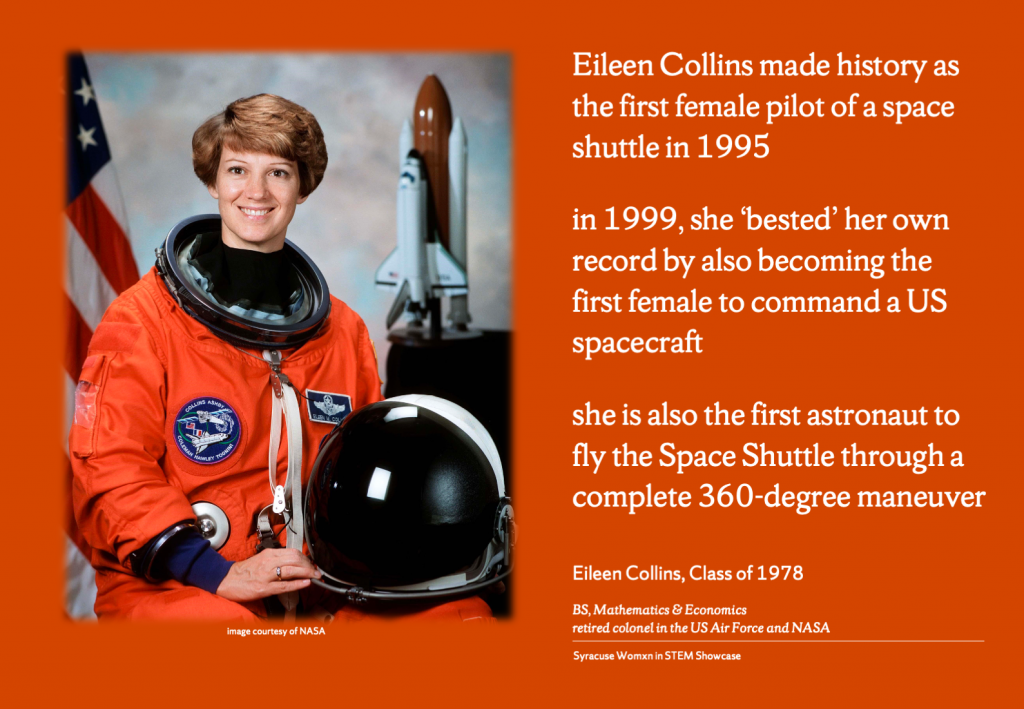

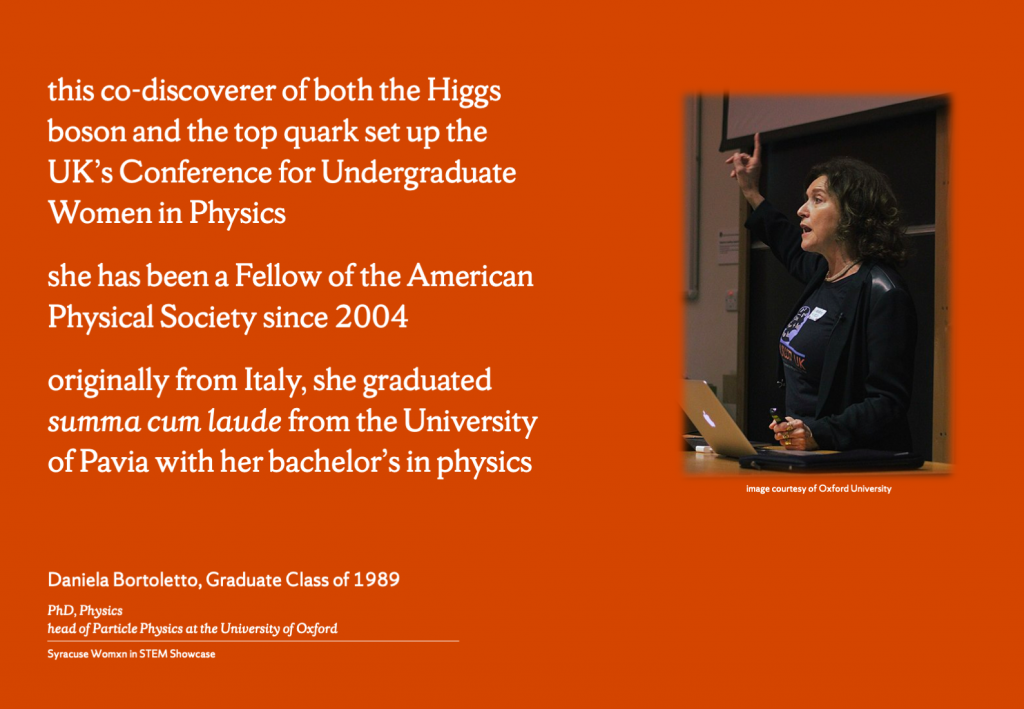

The history of womxn in STEM in Syracuse is thus a diverse and exciting one. The University’s very first commencement included Mary L. Huntley, who earned a bachelor of science. The school graduated the United States’ first female PhDs in botany and biology, the first woman to win the Perkin Medal for chemistry, the first female commander of a space shuttle, and the co-discoverer of the Higgs boson and top quark elementary particles.

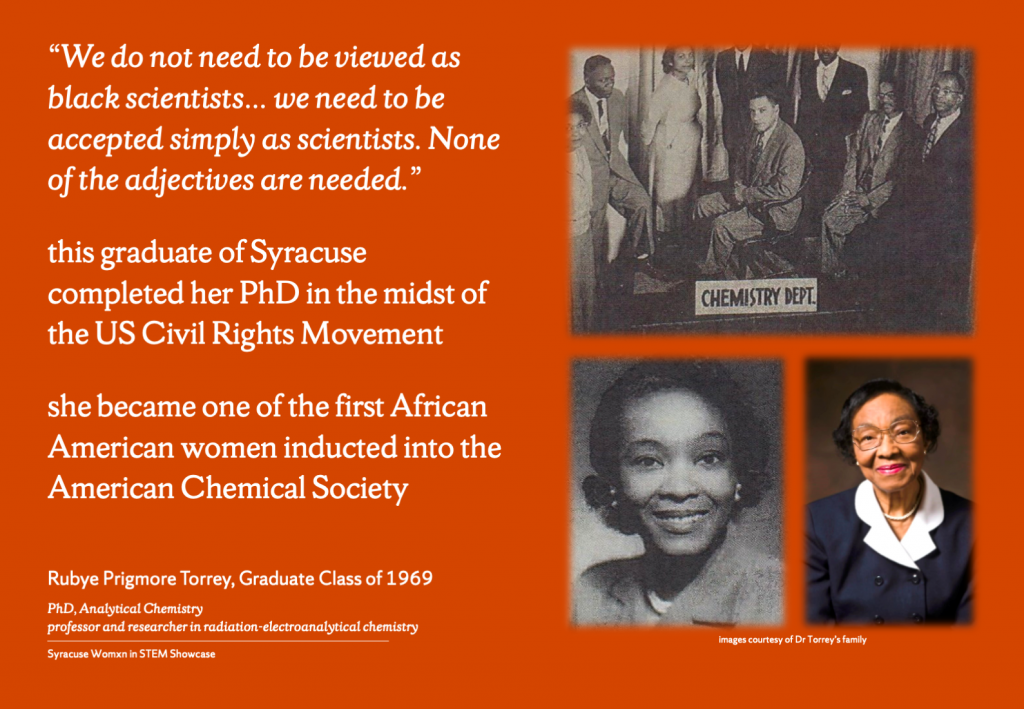

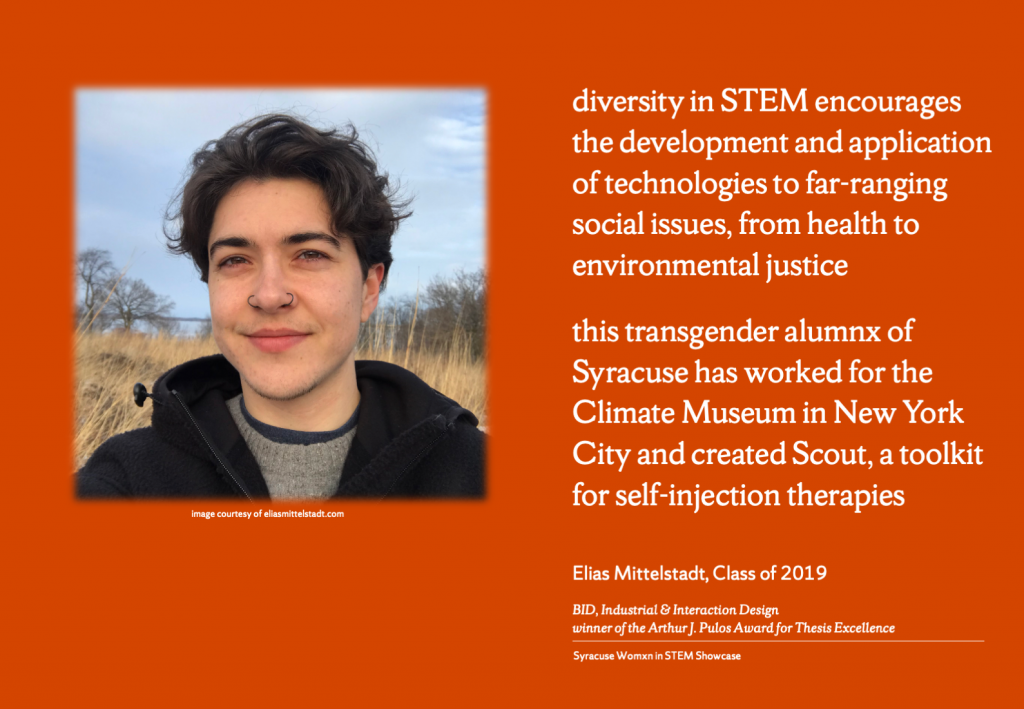

Despite the amazing accomplishments of many alumni, Syracuse’s history isn’t exclusively positive. Bias against persons of colour, Jews, Muslims, international students, women, and LGBTQ individuals is all too common, in and out of the laboratory. #NotAgainSU events reflect global problems of marginalisation and discrimination. As Syracuse marked 150 years, the UK honoured LGBT History Month, and the world observed the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, this Symposium was about celebrating the good, acknowledging the bad, and learning from the ugly.

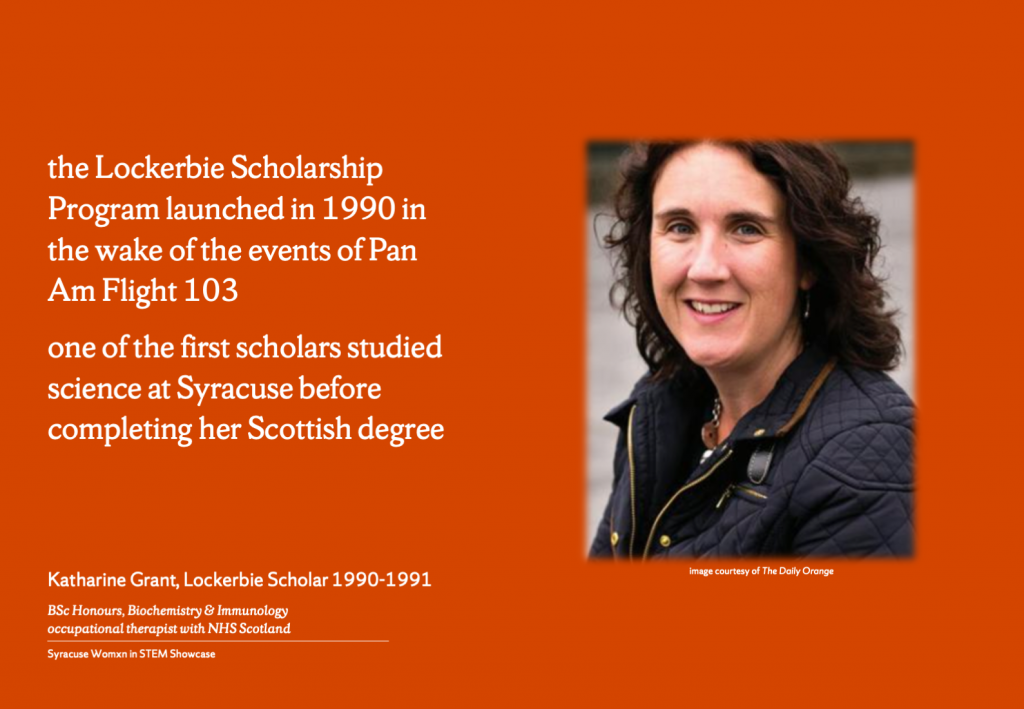

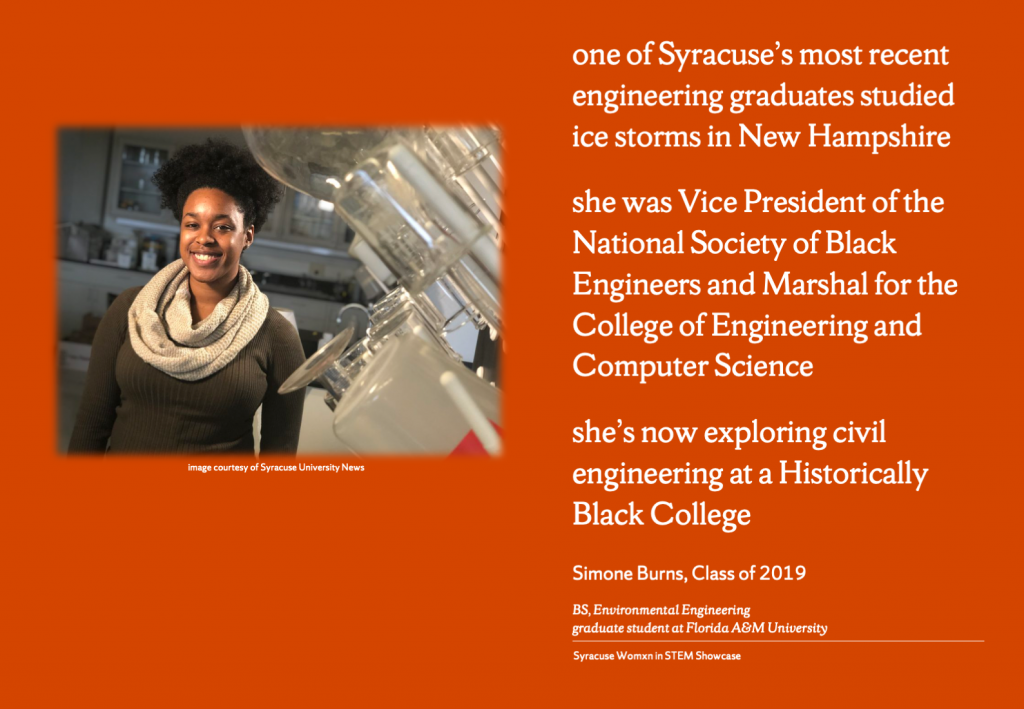

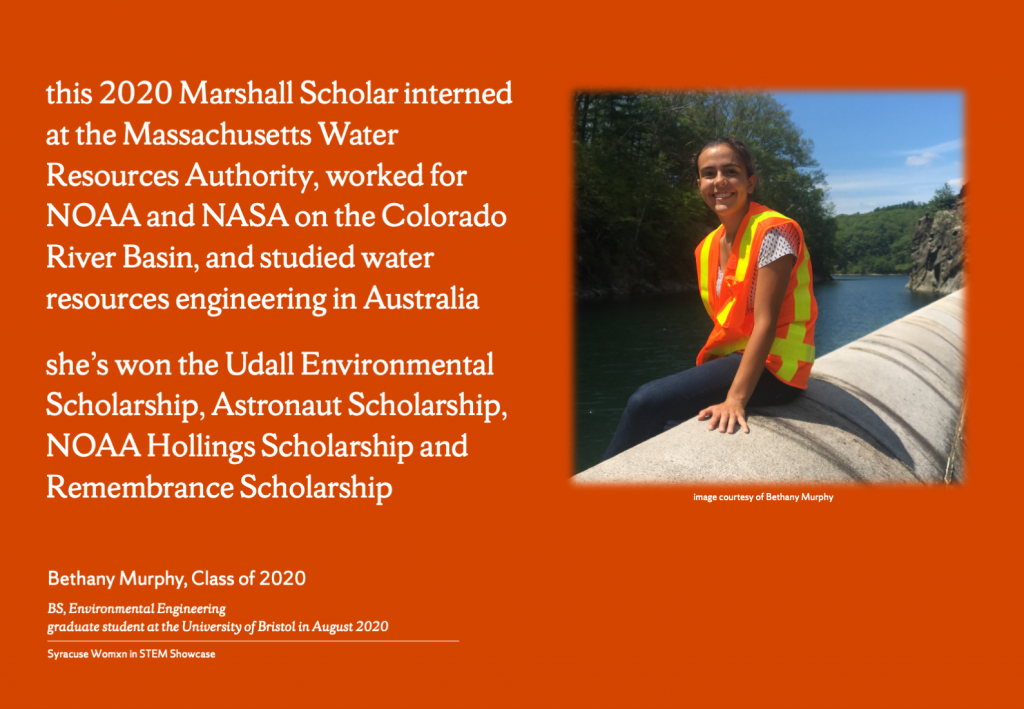

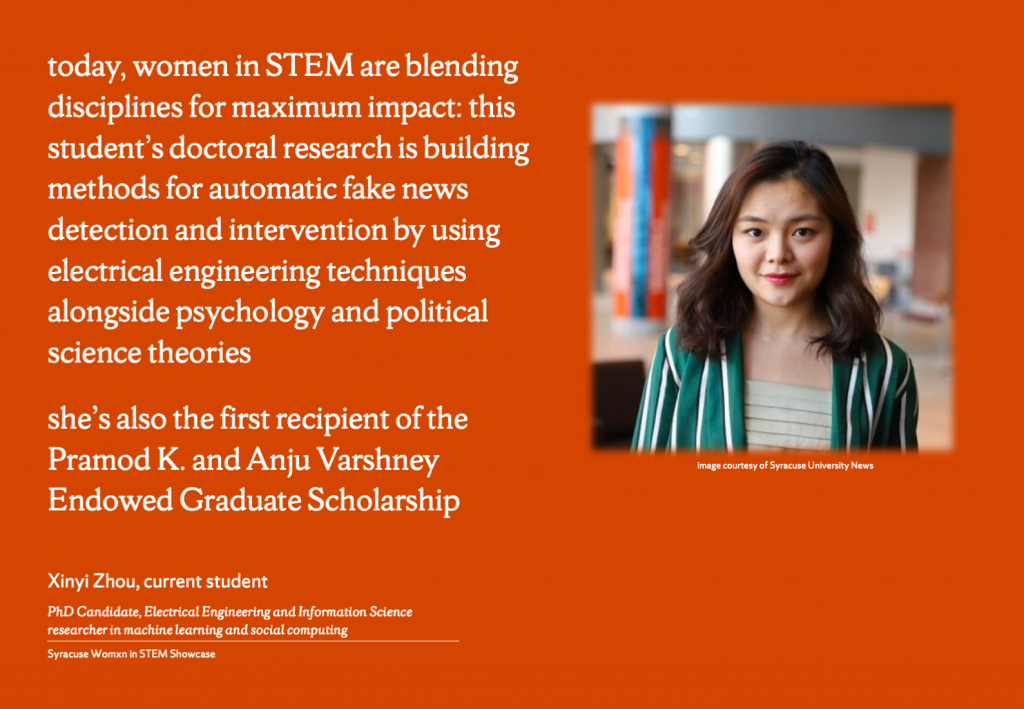

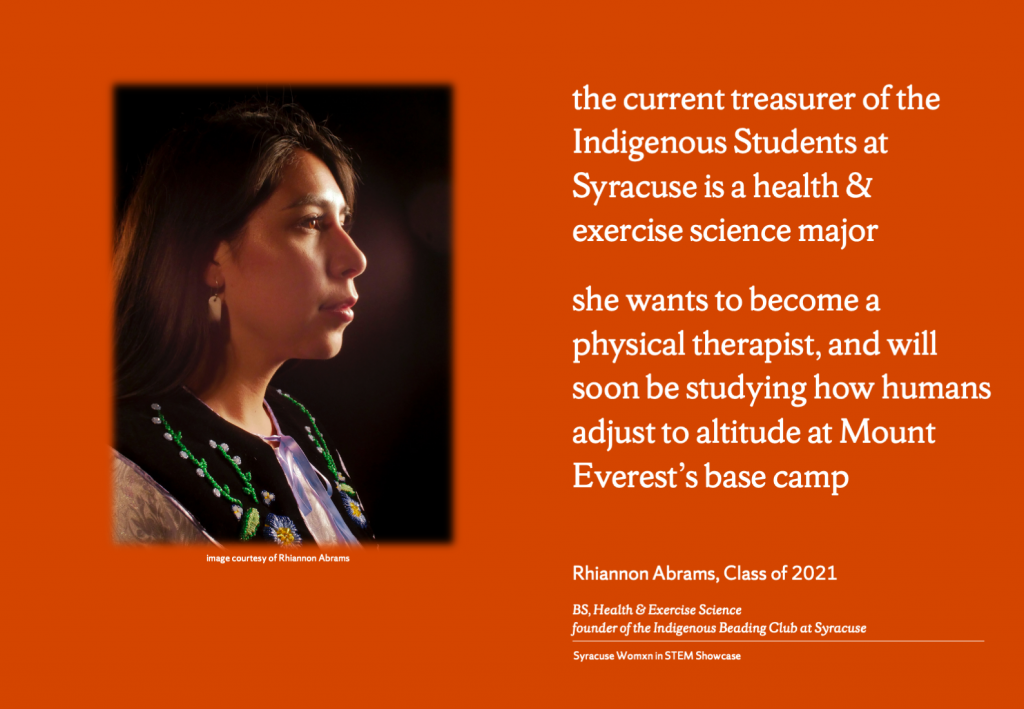

Syracuse London was privileged to have four Syracuse womxn in STEM sharing their experience as part of the evening: Katharine Grant, one of the University’s first Lockerbie Scholars and a lab scientist-turned-occupational therapist for NHS Scotland; Simone Burns, 2019 environmental engineering alum now in grad school at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering; Bethany Murphy, water scientist and 2020 Marshall Scholar; and Rhiannon Abrams, a Haudenosaunee health and exercise science student who studied abroad at the London Center in Spring 2020.

After opening introductions, attending students asked a series of questions informed by Syracuse history.

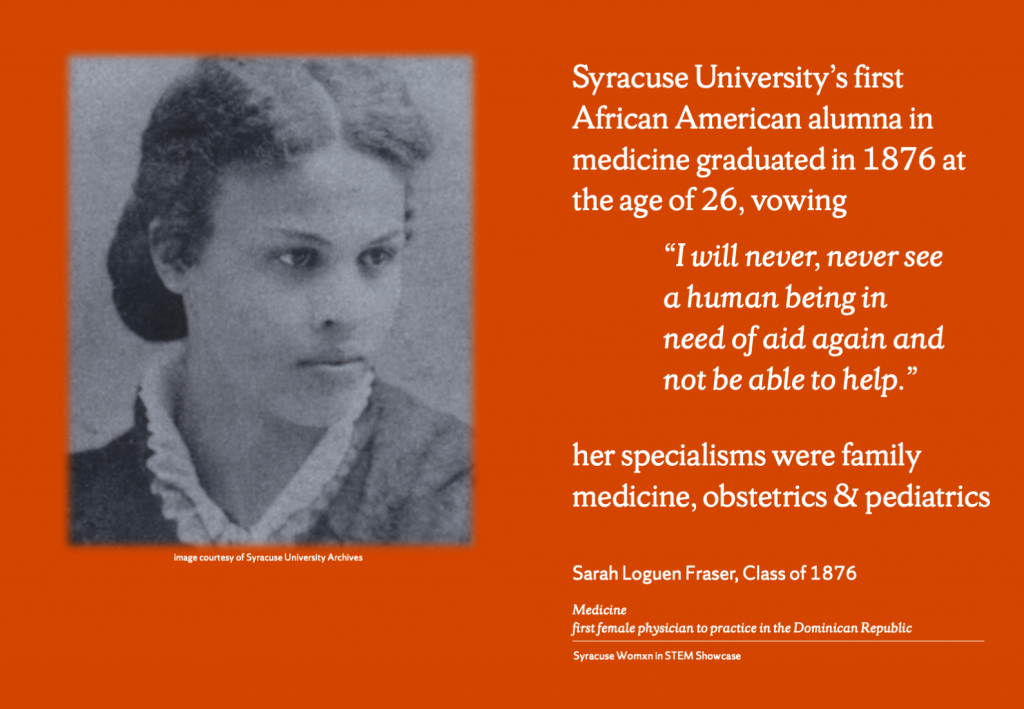

Sarah Loguen Fraser was the daughter of an abolitionist who had escaped slavery. The fifth of eight children, Sarah and her family gave shelter to nearly 1,500 persons escaping slavery on their journey to safety in Canada.

Her career ambitions were motivated by a tragic accident in her childhood, when she witnessed a young boy pinned beneath a wagon. Deciding to go to medical school, Sarah vowed:

What issue most drives you to do the work you do?

panellist Katharine Grant: “The belief that everyone should have the opportunity, support, and encouragement they need to live life to the full.”

panellist Bethany Murphy: “One of my geotechnical engineering professors, Dr Shobha Bhatia, has been just named a Geolegend by the Geoinstitute. She has been very involved in initiatives for women in STEM, opening doors for students like me.”

In 1986, Priscilla Tyree Williams – now City Construction Projects Administrator for the City of Raleigh – became the first African American woman to graduate with a civil engineering degree from Syracuse. But it was hard. Thinking about her time at the university and the resources available to her, Priscilla says:

panellist Rhiannon Abrams: “We can all point to snide sexist comments, but for me the lack of representation is what is most difficult — never having people from our communities included in the curriculum is a major issue, especially for indigenous women. And it’s not because the role models and achievements aren’t there. It’s just that they’re not talked about.”

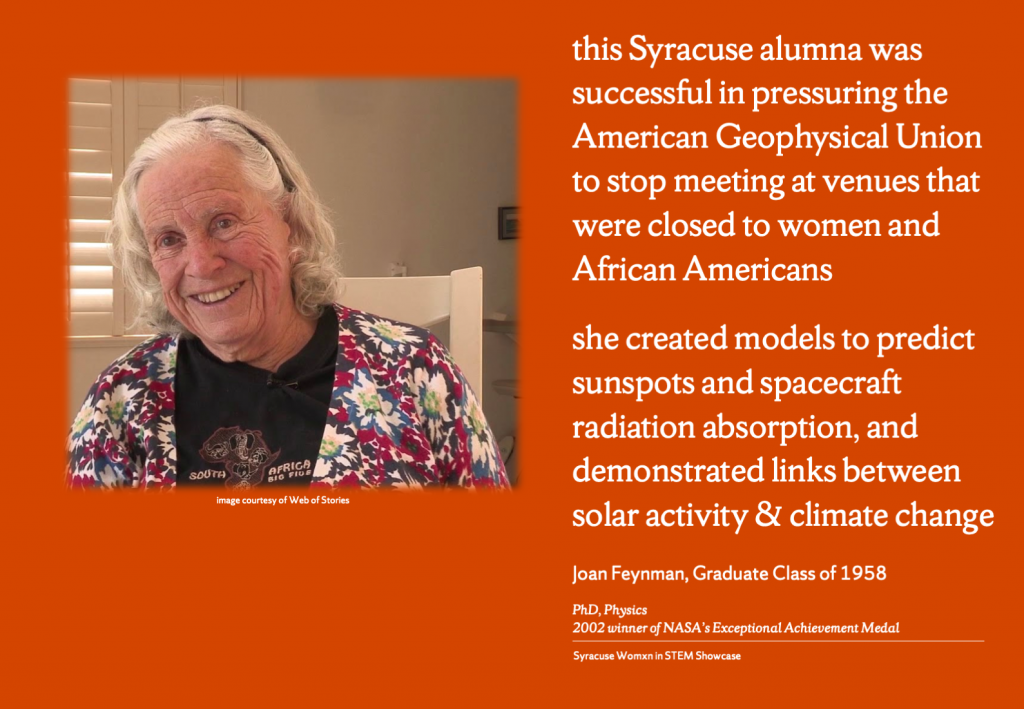

A few years before the Mandel Prize was established, another Jewish alumna received NASA’s Exceptional Achievement Medal for her work in physics. Joan Feynman graduated with her PhD from Syracuse decades earlier in 1958, before the Civil Rights Act passed when racial segregation was still legal in the United States. At the beginning of her career, Joan successfully pressured the American Geophysical Union to stop holding conferences at venues that were closed to women and African Americans.

Through their work, alums like Joan and Priscilla create space for others. What are some actions we all can take to support minorities in science?

panellist Simone Burns: “I have been so privileged to have amazing mentors and networks encouraging me along my journey. I hope to be able to be that for someone else someday.”

Elsa knows that womxn in STEM are still vastly underrepresented, and she regularly points out that

panellist Bethany Murphy: “One of my first memories of being intrigued by mechanics is playing with my retractable dog leash — thank you, Mary A Delaney!”

panellist Katharine Grant: “I’m from Scotland where it rains constantly…I have to say the windshield wiper!”

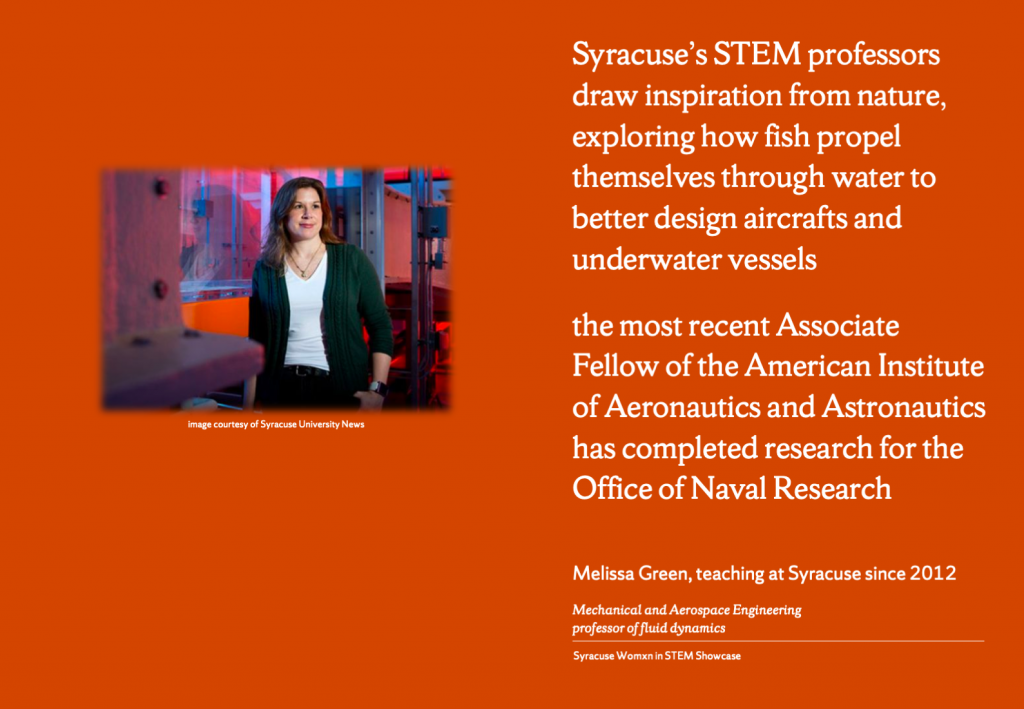

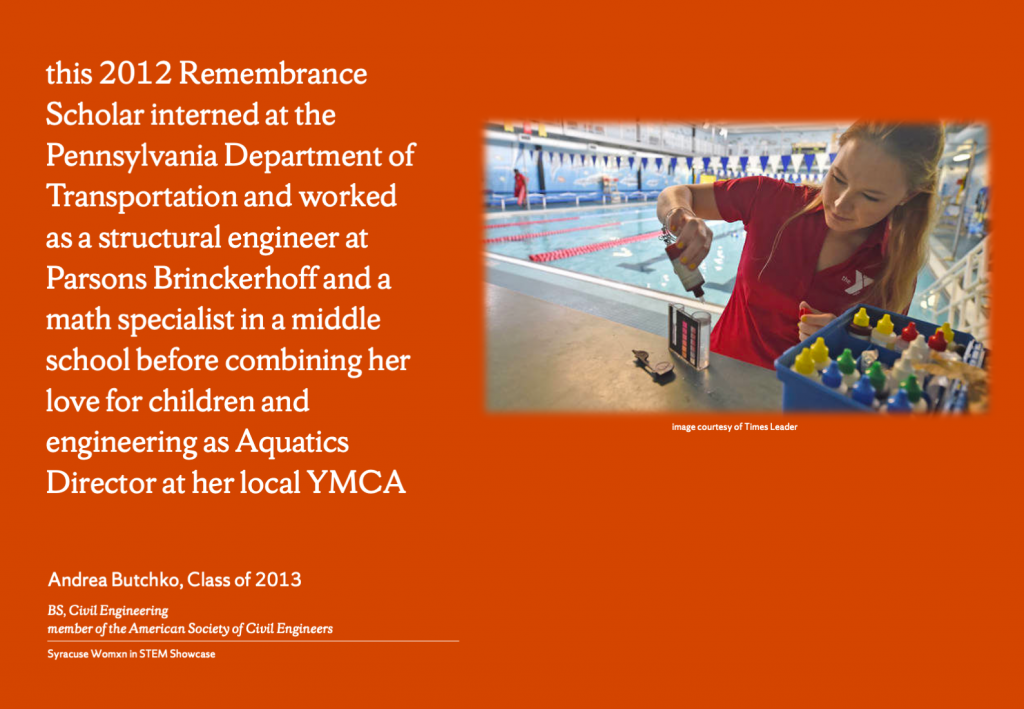

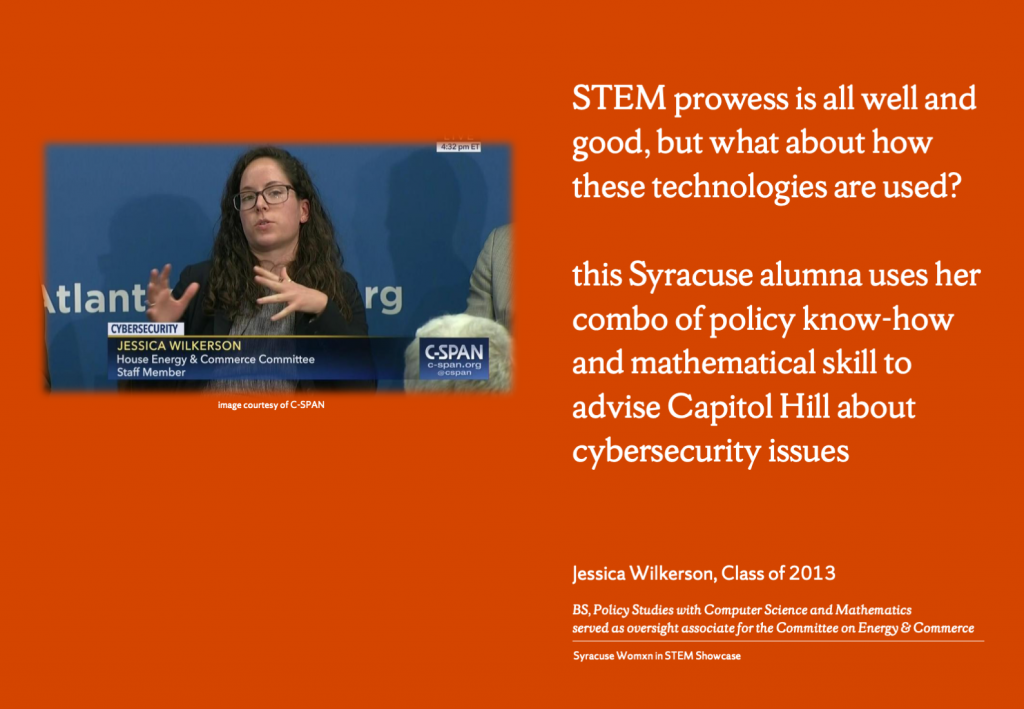

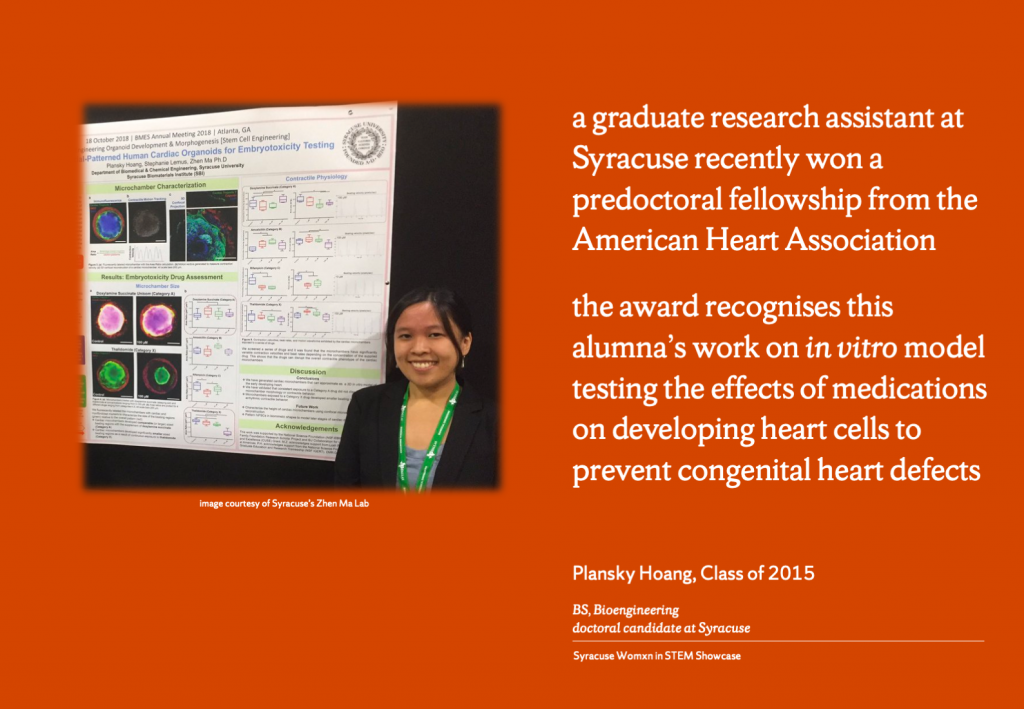

Learn about more womxn in STEM at Syracuse University:

You can download a PDF of Syracuse London’s “Womxn in STEM” Showcase here.