- See also:

- London’s Virtual Classroom, including:

Syracuse London Architecture alumna writes abroad-informed thesis

In Spring 2019, Ashley Nowicki studied abroad as a graduate student participating in London’s special program for architecture. At the beginning of her semester, Ashley travelled to Flåm, Norway, with a Syracuse Abroad Signature Seminar. A unit on ecotourism in that mountain village whose small population of four hundred hosts ten thousand tourists a day during peak seasons sparked Ashley’s interest in travel infrastructure and the politics of heritage branding. Later in the semester, she travelled to Morocco with Dr Becca Farnum to continue her studies in sustainable tourism, visiting local initiatives like Amal’s training centre for women in hospitality services and Dar Si Hmad’s field school for fog-harvesting.

Ashley built on this work for her thesis, combining design with ethnography to examine tourism’s impact on the built city of Marrakech. Her report includes historical attention to the capital’s cultural evolution, spatial analysis of the space’s contemporary reality, and architectural speculation for the city’s future possibilities.

Cultural Partitions with Tourism: Divisions in the Red City

a graduate thesis by Ashley Nowicki for the School of Architecture, supervised by Dr Bess Krietemeyer and Hannibal Newsom

—Dean MacCannell, The Tourist

Abstract

Abstract

UNESCO has placed itself in a superior agency in this concept, as it designates what is to be claimed “Cultural World Heritage”. In these cases, UNESCO gives criteria for what they may deem cultural heritage, and once a site has been placed of their World Heritage list, they are required to abide by certain restrictions to remain on the list or they will be forced to resubmit for this designation of “Cultural World Heritage,” which typically involves architectural elements as cultural space delineators or cultural heritage objects. Although these designations are designed to protect cultural heritage, the designations themselves become objects of consumption for tourism.

One of these originally designated sites is the walled medina of Marrakesh, Morocco. This project uses the Medina of Marrakech as a case study for evaluating the restrictions placed on the World Heritage Sites from UNESCO, understanding how tourism affects the region due to this “cultural heritage”, and speculating on how the city could evolve without UNESCO restrictions. This thesis looks to be critical over the restrictions placed on cultural heritage sites and to reflect on architecture’s role in cultural heritage sites and tourism.

Background: Cultural Tourism

Cultural tourism is a modern phenomenon that must be defined first through the definition of “culture”. The Oxford University Press first defines it as a noun, being either “the arts and other manifestations of human intellectual achievement regarded collectively” or “the customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or other social group.” The actual origin of the word culture comes from the Latin word cultura, meaning ‘growing, cultivate’, whereas the concept most commonly used today wasn’t considered until the 19th century. Culture as a verb can be defined as “maintain (tissue cells, bacteria, etc.) in conditions suitable for growth”; while referring to culture in a biological sense, it more easily relates to the origin of the word culture as well as defines culture as an action rather than an unchanging noun (culture becomes an object rather than an action). The concept of culture is the biological sense requires specific conditions and criteria in order allow for proper growth of the bacteria being investigated; if this concept is applied to communities, it would require a specific conditions in order for that community to grow as well, creating a complexity between culture and growth.

Dean MacCannell, in his book The Tourist, explores how tourism has evolved in the last century, both socially anc culturally, in this search for authenticity in other cultures that people believe have not aged into the falsehood of modernism. Through this search for authenticity, new issues arise within this social structure, as Dean MacCannell laments.

UNESCO

—Hernan Crepo-Toral

Although tourism and culture have become two entities that exist hand-in-hand, the purpose of cultural heritage must be evaluated for who this cultural heritage benefits versus creating negative affects of the space.

Marrakech, Morocco

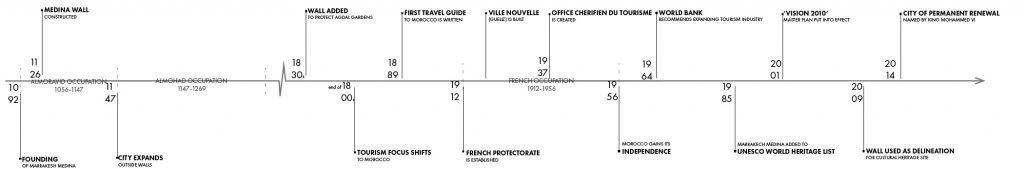

Claudio Minca in his chapter “Morocco: Staging Colonialism for the Masses” discusses Morocco’s history of colonialism and how tourism has affected the region, particularly Marrakech. Morocco as a whole has remained “an ‘exotic’ Arab and African destination for the European market”, starting with a tourism boom in the 1800s. Marrakech, itself, has a rich history with cultural tourism, being colonized by the French in 1912 and a new part of the town, Gueliz, being designed and built for French tourists soon after. Local and National Governments, along with organizations such as the World Bank, pushed for tourism even after Morocco gained its independence in 1956, establishing multiple different tourism plans such as the Vision 2010 plan in which Marrakech led as an example, striving for 20% of their GDP to be directly related to tourism.

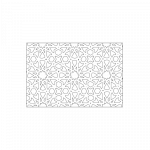

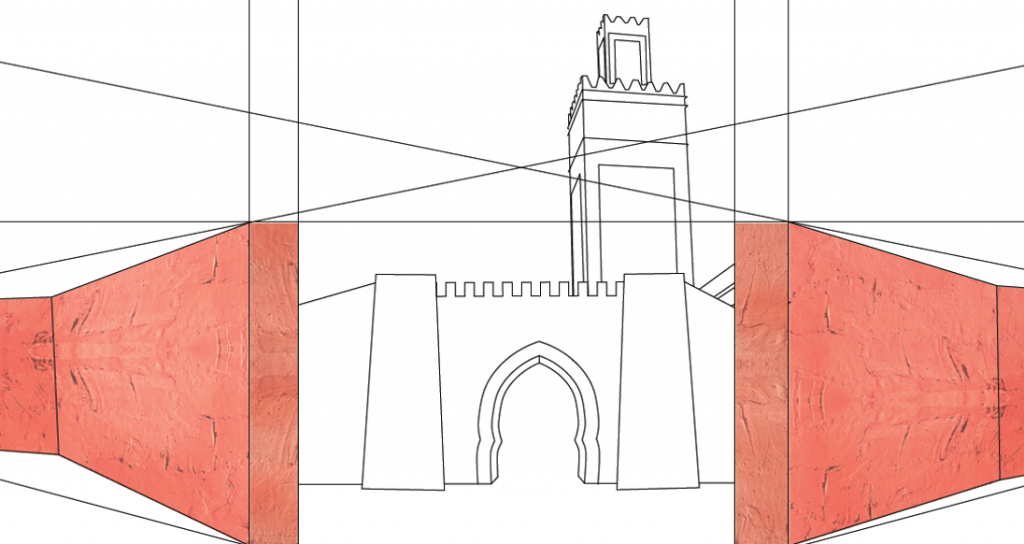

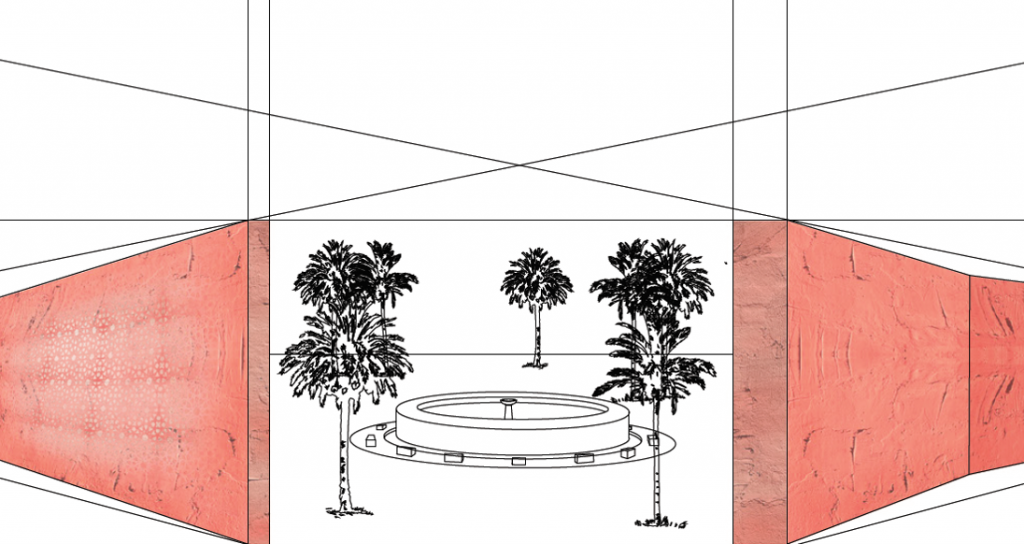

In contrast to the French-built Gueliz exists the Medina, built in the beginning of the founding of Marrakech through rammed earth construction. Notated in the white lines in the image to the left, the medina is the old islamic town of Marrakech nicknamed the “Red City” for the red clay the rammed earth buildings and Medina Wall is constructed from. The medina itself is a crowded part of the town with winding pathways throughout it, only big enough typically for people, donkeys, and motorized bicycles, creating a change in spaces in the old medina and the new parts of the city. The Medina Wall, sometimes referred to as fortifications or ramparts, lines the entire medina and encloses it. Originally built for defense in the beginning of the city of Marrakech, the Wall has now become part of the tourism and image of the city of Marrakech.

Marrakech itself exists as one of over one hundred walled towns on UNESCO’s list out of approximately 660 listed properties as of 2007 (Creighton 2007). Dr Oliver Creighton, a professor from the University of Exeter and archaeologist focusing on medieval castles and their landscapes, describes Marrakech and other walled World Heritage Site cities in Northern African as an “extreme clash with modernity” saying,

Like all walled cities on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list, the boundaries of Marrakech’s cultural heritage are demarcated by the medieval wall itself. Despite the cultural and historical events that have happened outside of the wall, UNESCO guidelines have only mentioned the idea of broadening the cultural heritage site — but have not changed the definition for the Medina of Marrakech: “The boundary of the property inscribed on the World Heritage List is correctly defined by the original ramparts that enclose all the requisite architectural and urban attributes for recognition of its Outstanding Universal Value.”

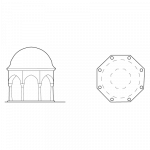

Along with the World Heritage Site inscription comes a list of rules and requirements for the site, such as: “Reconstruction and redevelopment work carried out in the heart of the historic centre generally respects the original volume and style. The use of traditional materials in these restoration operations has tremendously revived the artisanal trades linked to construction (Zellige, lime plaster (tadallakt), painted and sculpted wood, plastering, wrought ironwork, cabinetmaking, etc.) in addition to trades linked to furnishing and decoration.” If the city does not abide by these regulations, the medina can be removed from the World Heritage Site, thus also pulling funding from UNESCO for repairs and upkeep made necessary by tourism. Although the requirements for upkeep might be the most helpful for keeping the cultural heritage of the construction technique that was once used in the region, the medina has become unstable and at risk of collapse, risking lives of people within the medina (see image to the right).

Along with the World Heritage Site inscription comes a list of rules and requirements for the site, such as: “Reconstruction and redevelopment work carried out in the heart of the historic centre generally respects the original volume and style. The use of traditional materials in these restoration operations has tremendously revived the artisanal trades linked to construction (Zellige, lime plaster (tadallakt), painted and sculpted wood, plastering, wrought ironwork, cabinetmaking, etc.) in addition to trades linked to furnishing and decoration.” If the city does not abide by these regulations, the medina can be removed from the World Heritage Site, thus also pulling funding from UNESCO for repairs and upkeep made necessary by tourism. Although the requirements for upkeep might be the most helpful for keeping the cultural heritage of the construction technique that was once used in the region, the medina has become unstable and at risk of collapse, risking lives of people within the medina (see image to the right).

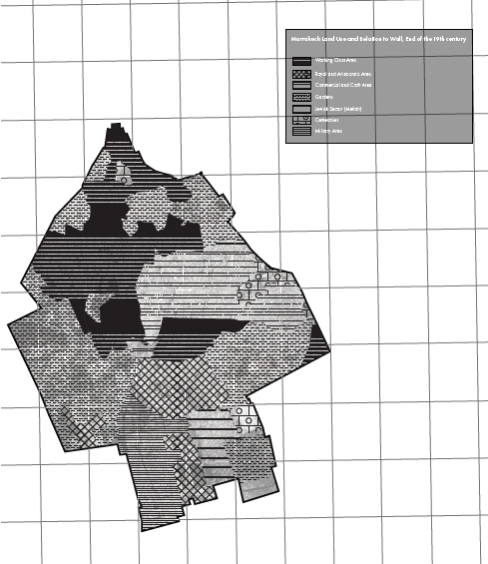

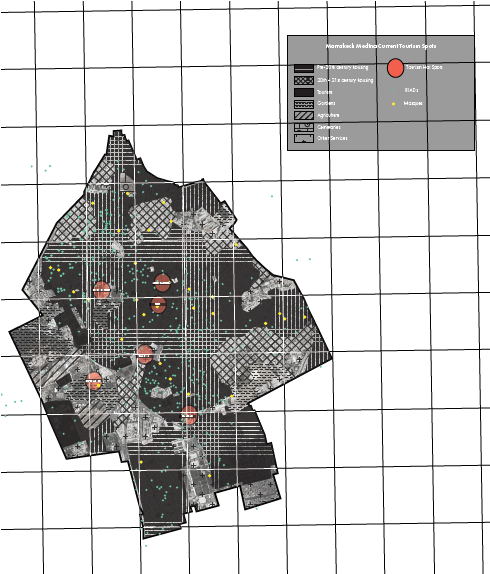

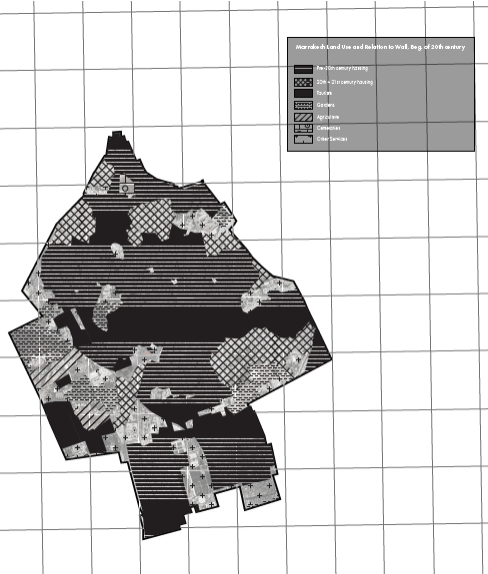

This was one of many issues that Anthony G. Bigio from The World Bank found within Marrakech during his analysis of the medina in 2010, as well as concerns for traditional businesses losing their market share, rising rent prices in the medina for residents, and traditional local activities eroding as new stores open for tourists. The maps below show great changes in urban land use between the end of the 19th century and the end of the 20th century, most of the shifts related to tourism within the medina itself.

The wall itself has become the spatial divider for in which major cultural tourism happens, where the amplification of what is expected to be “Moroccan culture” happens as the “Moroccan” product is staged for the tourist within the confines of the red clay wall that lines the medina. It exists as both a historical and cultural symbol of the medina and a confiner for the ability for the community to grow or change. As UNESCO delineates the wall as a necessary boundary of the cultural heritage of the medina, as well as a major part of the Outstanding Universal Value of which Marrakech is as a cultural entity, the question arises:

Can the wall absorb the tension of tourism and staged authenticity in the medina,

becoming new space for this necessary economic factor of the city?

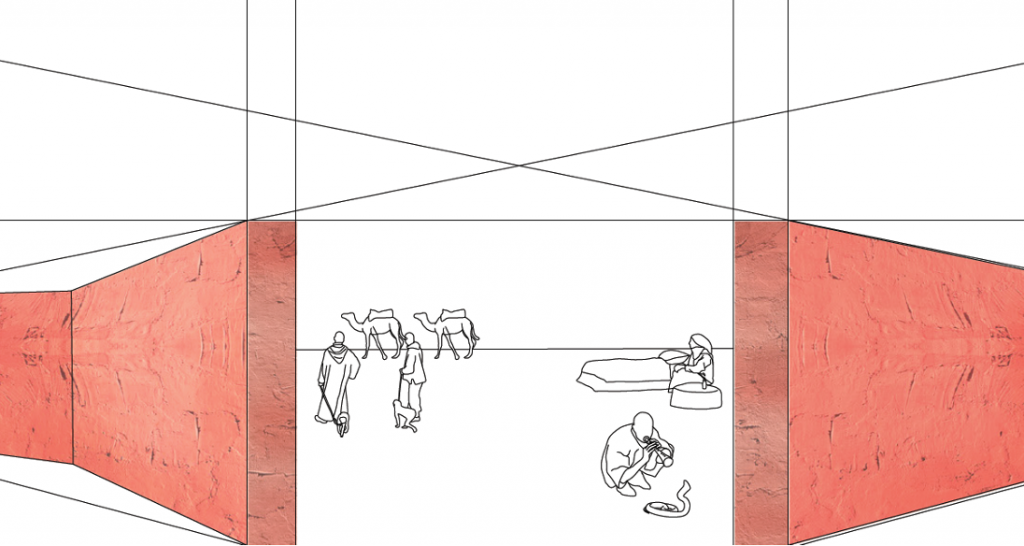

Conditions around the wall change as it unwraps, where parts expose crowded housing within the wall in contrast with parking bus depots, taxi depots, and newly developed market places for the locals on the outskirts of the wall. These conditions show potential for new development and use of the wall itself for the community.

Approach

The objective of this research was to gather learn how architecture has played a role in cultural tourism in the medieval town of Marrakech, Morocco and to speculate on how architecture could create new realities within this medina. The Wall become a unifier of all research issues: historical, cultural, tourist-based. When the research showed that the Wall was marked as as the spatial divider of “Cultural Heritage” under UNESCO, the Wall became the key tool to be used to in this speculation, and the key component to wrap the research and maps around. Both past and future, questions were framed around the wall, such as “How have conditions developed around the wall?” in research, and “Can the wall be extruded and thickened to become a new condition of the medina?” in speculation. With the Wall being the main framing device, UNESCO became the audience for this research and speculation.

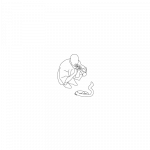

The research was gathered both primary, through some minor fieldwork, and secondarily, through research articles, publications and mapping softwares. The initial thesis topic was discovered on a visit to Marrakech with Professor Becca Farnum, in which, both, locals voiced concerns for the misuse of their Moroccan culture with means of tourism and economics, as well as locals creating makeshift signs and directing us back to the main paths of the medina, telling us there were certain parts of the medina we were not supposed to be in (see photo to the left). These experiences eventually led to inquiry into myself as a tourism as well as how the tourism industry was affecting this city and more.

The research was gathered both primary, through some minor fieldwork, and secondarily, through research articles, publications and mapping softwares. The initial thesis topic was discovered on a visit to Marrakech with Professor Becca Farnum, in which, both, locals voiced concerns for the misuse of their Moroccan culture with means of tourism and economics, as well as locals creating makeshift signs and directing us back to the main paths of the medina, telling us there were certain parts of the medina we were not supposed to be in (see photo to the left). These experiences eventually led to inquiry into myself as a tourism as well as how the tourism industry was affecting this city and more.

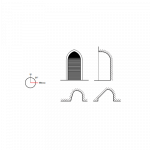

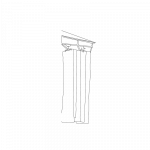

Secondary research was conducted by evaluating the history of the Wall and tourism, the conditions around the Wall, mapping the medina under changing land-use, and evaluating different types of Moroccan architecture and elements. The conditions around the wall were evaluated both through mapping and through unrolling of the wall into an axonometric drawing of the space and conditions directly involving it. Analysis of the conditions of the wall and speculation on the future of the wall led to rezoning the wall of the medina.

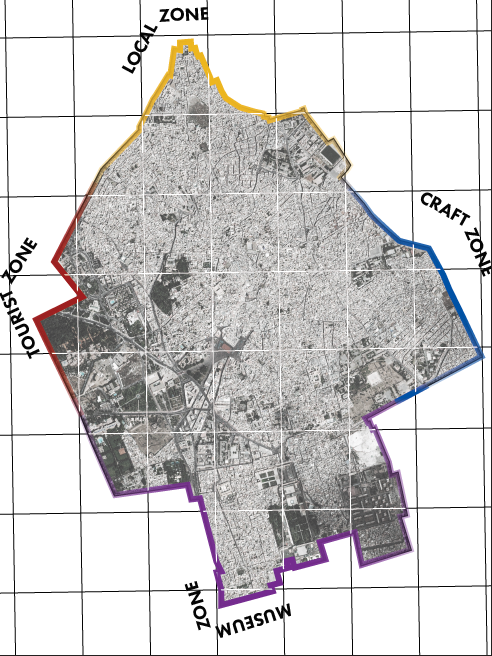

The Wall was rezoned into four new sectors: Tourism, Local, Craft, and Museum.

The Tourism Zone is located near the bus station and taxi services typically used by tourists and near the main square of Marrakech, Jemaa el’Fna, a main attraction for tourists.

The Local Zone is located where mainly local residents live and where local residents have begun a local souk or bazaar for the region outside the wall (located in the north of the medina).

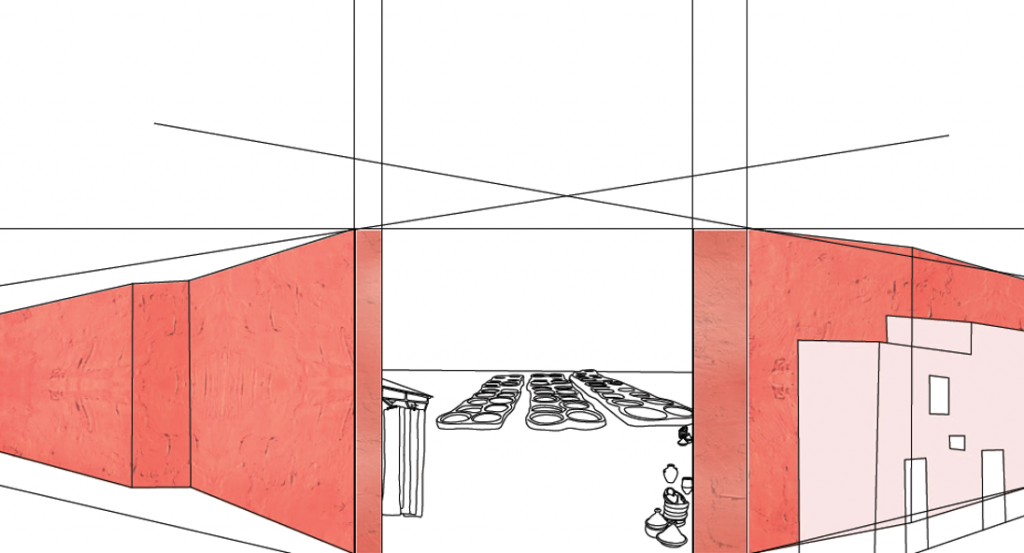

The Craft Zone is located on the eastern side of the wall where the tanneries were found to have moved to along the wall. Although these tanneries are not in any major tourism region of the medina, there are still many private tours of the tanneries offered to visitors. Research has shown that these crafts once existed in the center of the medina and were pushed to the outskirts of it after the center was transformed for tourism.

The Craft Zone is located on the eastern side of the wall where the tanneries were found to have moved to along the wall. Although these tanneries are not in any major tourism region of the medina, there are still many private tours of the tanneries offered to visitors. Research has shown that these crafts once existed in the center of the medina and were pushed to the outskirts of it after the center was transformed for tourism.

The last zone, the Museum Zone, is in the south of the medina near the Bahia Palace and the Kasbah. Here, there exists a museum space to tell the history of Marrakech’s medina.

From this point, a research catalogue of elements was developed for the zones. These elements were used in speculation of what could happen within these zones of the Wall, in which these uses could attract tourists and locals of the medina.

Research Catalogue: Land Use Elements

Speculations: Zones within the Medina

Discussion

The results of this project speculate on new possibilities of conditions within the wall. The wall itself can become a new economic zone for the medina, enwrapping itself the the aspects people consume of the medina when visiting it and potentially giving the center of the medina time to be revitilized in what the locals may seem fit. The main conclusions under this project came with the questions of “Where is the threshold between preservation and progress?” and “What are the benefits of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Designations?”

In regards to the first question, there is no clear delineation between when to preserve and when to progress, but certain cities, such as Istanbul, have been exploring this concept while being on the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Although there is a concern for preserving history of cultures, there also needs to be an equal concern for the all stakeholders involved in the designation of these sites. In regards to Marrakech, there does not seem to be a large amount of powere or agency given to the local residents of the medina and this should be a concern of agencies such as UNESCO when designating such sites. Agencies as large as UNESCO have the ability to bring power and agency back to the people that are often not heard from and they should use their abilities to do this.

Considering the second question, UNESCO World Heritage Site Designations not only give sites an important global status, but also give sites monetary incentives and grants to keep the World Heritage Site in certain good conditions. In certain places like Marrakech, the financial incentives are helpful, but the requirements to upkeep a certain older construction method has remained detrimental. Although the construction method is part of the history of the Wall, the wall itself is constanly in need of repair, as well as the homes within the medina. Looking at the UNESCO guidelines, the image of the history of the medina could be perceived as more important than being completely accurate to the site, as it seems to become more of a memorial of what used to be Marrakech. If UNESCO World Heritage restrictions were removed from the medina, there could be serious concern of loss of cultural heritage of the site, but by speculating on the removal of the restrictions on the medina we can speculate on how the restrictions could potentially be adapted to preserve the cultural heritage of the city while also allowing walled cities such as Marrakech the ability to progress and grow as a community.

The concept between preservation and progress does not have any clear answers on how to go address the ongoing issues, but it is important to be critical over how restrictions and designations are affecting communities at large. Although cultural heritage is typically understood to be “saved” to keep cultural documentation of certain groups of people, cultural heritage has mainly become involved in tourism that has actually led to inauthentic representations of cultures of the communities in which people are visiting. When being critical over the designations of these sites, we should be questioning who we are preserving the site for, why we are preserving it as well as being concerned of potential negative outcomes of the designation that may affect the community of the site.